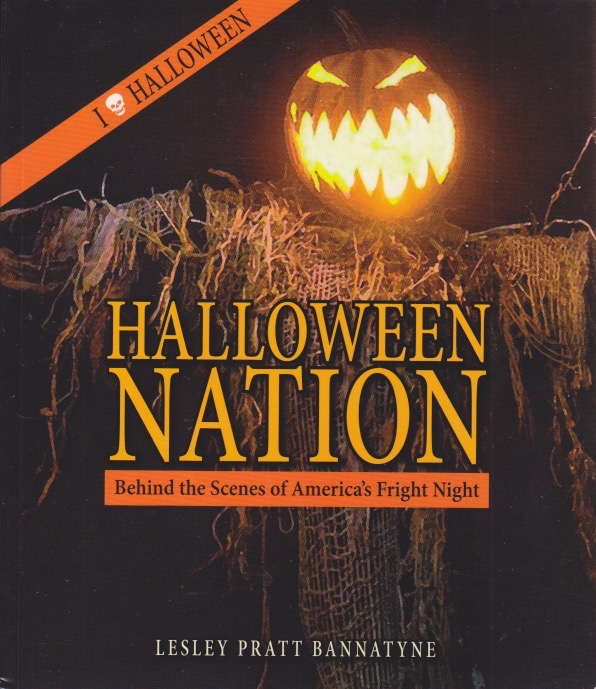

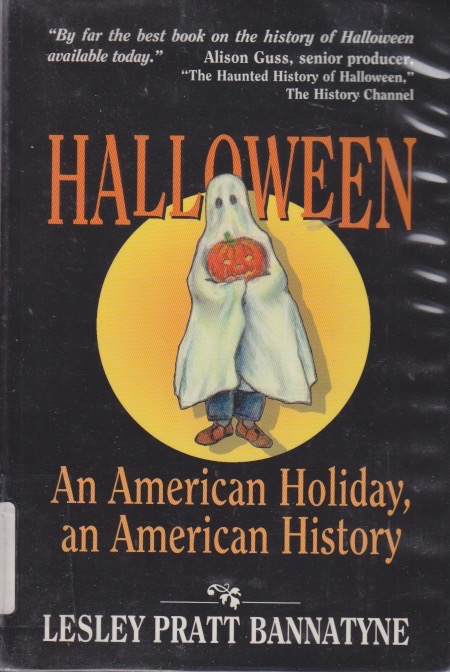

It’s a strange but strong connection. Between Halloween and me, that is. I’ve always loved the holiday. I don’t like being scared, however, and gory horror movies aren’t my favorites. Still, I’m not alone with my fascination. Lesley Pratt Bannatyne has written a couple of thorough books on the holiday. Halloween Nation: Behind the Scenes of America’s Fright Night looks at various aspects of Halloween as it’s celebrated in America. It’s both an imported and exported holiday, of course. The raw materials came in mostly from Celtic countries—Ireland in particular—and got mixed in with other traditions here before being sent out to the rest of the world as it’s now known. The thing about Halloween, or any holiday, is that it’s impossible to capture all of it in a book. Halloween has many associations and a good few of them are explored here. Halloween’s in the air as retail stores know. So let’s take a look.

Bannatyne’s chapters on ghosts, witches, and pumpkins are particularly good. The pumpkin connection, which is an American innovation, is particularly telling. It’s been a few years since I’ve carved a jack-o-lantern, but it is one of the fond memories of childhood. The challenging orange palette that has a wonderful evocative smell and feel. Bannatyne gives good information about pumpkins and how they’ve become central to the holiday. Indeed, the symbol that gives Halloween away is the jack-o-lantern. I found many little gems throughout the book.

Halloween Nation is amply illustrated, in full color, no less. Bannatyne has a good idea of what Americans do for fun. Capturing the fulness of the holiday in one book may be impossible, but here you’ll have tours of zombie walks, fan conferences, the Greenwich Village parade, over-the-top haunted house attractions, naked pumpkin runs, and pumpkin beer breweries. You’ll learn about the history of trick-or-treating and how grown-ups came to embrace what really took off as a day for childish pranks. Halloween is an expansive occasion. Holidays also have their own local flavors. My early memories are of small town celebrations where even poor folk like us could join in the fun. Nashotah House, for all its problems, did Halloween well when I was there. To really do it right takes time that seems difficult to come by these days. It’s just as easy to cue up a horror movie and promise to do better next year. Still, every year I hope to cut through the jungle of obligations and give the holiday its due. It’s usually a work day (Tuesday this year), but at least now I’ll be better informed about what I wish I were doing instead.