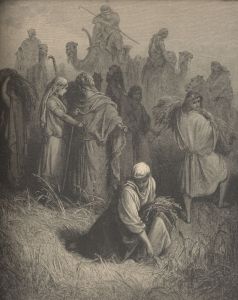

I’ve been reading about Ruth lately. Ruth doesn’t have a last name. She’s a character in the Bible. The book named after her is one of the shortest in the longest, Hebrew section of the Good Book. It’s a fairly gentle story, although it has a body count. Ruth, a Moabite, marries the son of an expatriate Israelite. This was in the days before the West Bank, but there was still some distrust there. Widowed Ruth moved to Israel with her equally widowed mother-in-law, and supported this non-traditional family by gleaning. Unlike modern civilization, shop-lifting (or field-lifting) by the poor was not a misdemeanor. In fact, the Bible insisted that it be allowed. It turns out that the field she’s been gleaning from belongs to a relative who eventually marries her via a tradition known as levirate law. Again, this is something current family values oppose, although it is commanded by the Almighty. Levirate law stated that if a man died childless, his younger brother had to take his wife until they had a child in the name of the dead brother. Creepy, but practical. A widow, in those days, had to have a child to support her.

I can’t recall when I learned this was called levirate law. I started reading the Bible before I was a teen, so I knew the story, although I didn’t understand the finer details. It was probably in the heading of some Bible translation that used the word “levirate” that I first encountered the term. I assumed it had something to do with the Levites. I mean, the words share the same first four letters, and Levites were all over the place in the Bible, even if they cross to the other side of the road. So it was that I went for decades with the idea that marrying your brother’s wife, at least temporarily, was because of the Levites. Nothing in the Bible said that Levites did this, and other than the jeans, I didn’t know any other Levi words.

Recently I learned that this is a false etymology. Levirate comes from a Latin root for “brother-in-law” and not from a Semitic root meaning “half-priest.” It may sound strange, but this was a genuine shock to me. I’d never told students that the word came from Levi, but I assumed that anyone could figure it out. After all, things that sound so very similar must belong together, right? Well, I admit to having been wrong here. The story of Ruth, however, is one of the true gems of the canon. Men play a minor role, and it is a woman who shows the way. It is a tale for our time. Family values, according to the Bible, aren’t always what they seem.