In order to have this book fit my blog, I’ll begin with a spoiler alert. If you plan to read Cat Winters’ The Uninvited, I will be giving away information below. Please believe me when I say it’s not intended to be persnickety by this preface, but I know what it’s like to enter a book knowing too much.

In order to have this book fit my blog, I’ll begin with a spoiler alert. If you plan to read Cat Winters’ The Uninvited, I will be giving away information below. Please believe me when I say it’s not intended to be persnickety by this preface, but I know what it’s like to enter a book knowing too much.

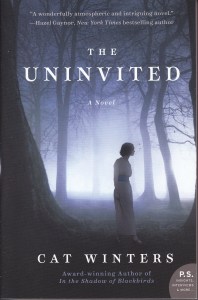

When autumn comes around I like to find a ghost story or two to read, to settle into what seems to be a primal urge connecting harvest with death. Sometimes the books I find are advertised in places like the Library Journal, or Publishers Weekly (which I see more like biannually). More often than not, however, they are books that I spy at a store. The Uninvited stared at me from a table. I picked it up, read the blurbs, and put it back. A week later I stopped in again and picked it up. It is a moody tale set during the First World War and the influenza epidemic. That was a time, I suspect, of great fear. And many ghosts. It’s easy to see why Winters chose such a time to set a tale. Still, the narrative is gentle and despite the places where the language sounds too modern, it is artfully told. Like most ghost stories it is a love story. Seriously folks, here come some spoilers!

The protagonist, Ivy, falls in love with Daniel, a German immigrant living in Buchanan, Illinois during the war. Germans have been under suspicion and lynchings have occurred. We come to learn, as in many ghost stories, that the protagonist and her lover were both victims—he of a lynching, she of the flu. He’s aware they’re dead, she’s not. The novel is one of Ivy’s growing self-realization that she’s deceased. While avoiding those who spy on Germans, she discovers the joys of an interracial, prohibition-free (being prior to prohibition, of course, but the idea was in the air) club where jazz is played all night long. She wants to bring her lover to the club, which is just across the street from his apartment, but he is German and feels he would not be welcome. The reader at this point doesn’t realize the two are dead. Once Ivy discovers the truth, she realizes that the club is actually Heaven. The reluctant ghosts, lost, stay away. She tries to convince them to come.

Heaven has been portrayed in many ways in literature. Although I find jazz very difficult to bear (it is like being inside a beehive without a bee suit, to me) the idea that Heaven is complete and utter acceptance of who we are is a compelling one. Religions are often all about change—how we must alter who we are to merit Heaven or Nirvana or whatever might await us at the end. Winters suggests that it is a place where people can be who they are and nobody will try to make you be any different than you were created. It is a comforting idea. It is my personal hope, however, that there might be a few different clubs in town and that some of them might be playing music other than jazz.