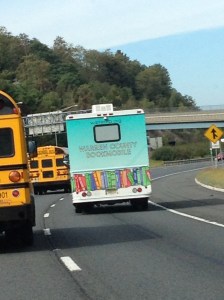

Some unexpected serendipities transport you to childhood. Somewhere on Interstate 80 I passed a bookmobile. The notion felt strangely old-fashioned in this days of Nooks and Kindles. Indeed, a Kindlemobile would have been no less surprising. The idea, I recall, that someone cared enough about my little school to drive a bus full of books right up to it, made me feel special. I mean, these were books—for me! I don’t recollect ever checking any out since it was the ’60’s and everything communal had a strangely communist cast to it. We couldn’t afford many books. Indeed, growing up, we didn’t have a proper bookshelf anywhere in the house. When I began to buy books, I kept them in a cheap suitcase. The only trips I made, really, were in my mind.

In Manhattan I occasionally see the Mitzvah Tank. New York is often thought of as one of the most literate cities around. Even here, books can come to your door. With chutzpah. Religions, at least many of them, coalesced around books. Sacred writings are among the omnipresent symbols that you’ve come into religious territory. The act of writing itself is somehow holy, even to the most secular, beyond the most cynical. We share our minds through our fingers and others are invited to see, or at least to glimpse, what might be going on inside this three-pound universe locked in our craniums.

What would I put in a bookmobile? The other day my family began putting together a list of the influential authors in our lives. We all read quite a bit, and the list grew lengthy rather quickly. What would be in the canon of a Bible for the twenty-first century? What books would we want others to share? Ironically, many would find religious books objectionable on some level or another. The armored personnel carrier of Christian soldiers might well set us on the run. Nevertheless, with enough reading even the extremes can be viewed in perspective. On this highway I’ve found a kindred spirit, and when books are coming your way, it is a mitzvah indeed.