Have you ever had one of those dreams? The kind where your subconscious turns on you brutally? I’ve often said I’m my own worst critic but this one took it to a whole new level. In real life I’m working on novel number eight. One through seven haven’t been published (and at least two don’t deserve to be). I’ve kind of been thinking that this one might see the light of day. I finished a very rough draft about a couple months ago and I’ve been working on revisions since. Meanwhile I keep reading novels and seeing how well they flow compared to my story. That must’ve been on my mind because in my dream I was in a room with five or six publishing moguls. In the way of dreams it seems that perhaps an agent had arranged this. I was in the room with them and when they finished, each took their turn telling me how awful it was. Their critique was brutal. So bad I couldn’t get back to sleep. I found tears on my cheek.

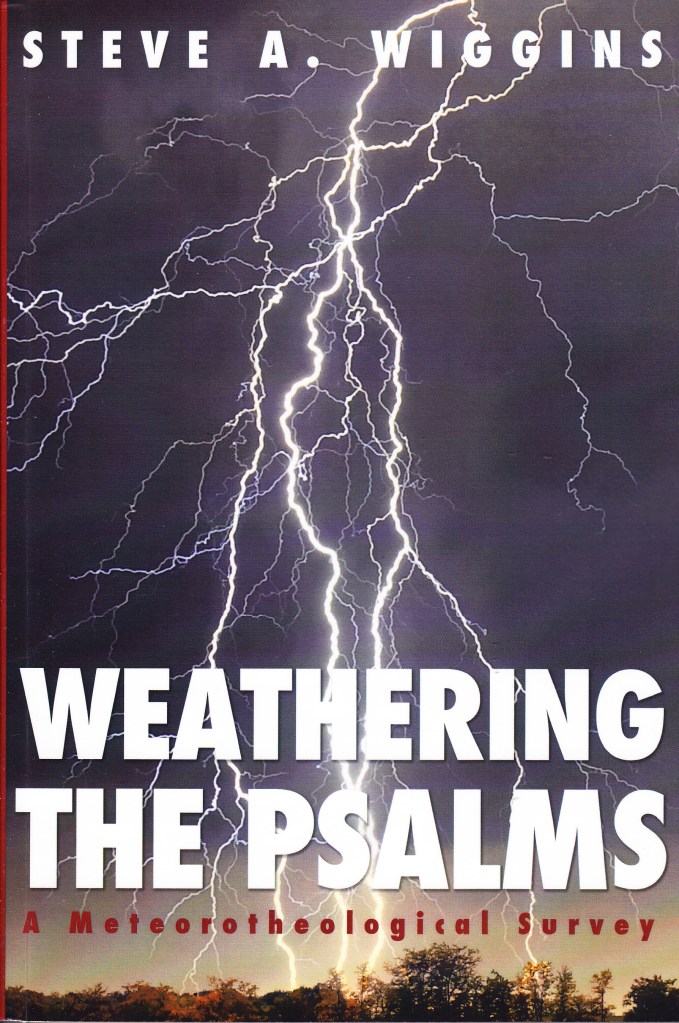

Of course, my writing time is early morning. Work is uncompromising. So I had to get up and work on what my subconscious had just told me was, in the words of Paul, skubalon. (Look up the commentaries on Philippians 3.8, if you dare.) Like any writer, I have my doubts about my own work. This particular novel I’ve been working on, off and on, for almost three decades. It’s an idea I can’t let go. Just a couple months back I was proud of myself for finally finishing a draft of it, and this morning I’m tempted to delete all the files. Why does one’s subconscious do this to a person? My very first attempt at a novel, as a teen, was torn up by my own hands.

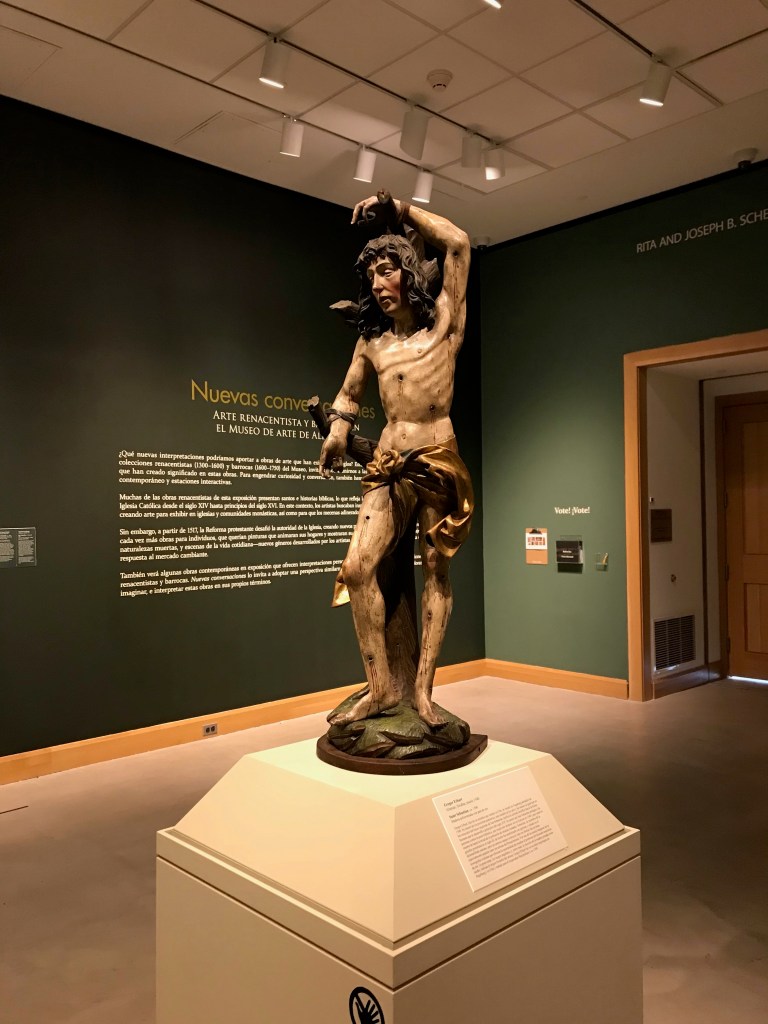

The other dream that has been recurring, in various forms, is where I’ve been hired back by Nashotah House. I taught there for a decade and a half, and I wasn’t very happy toward the end, but I did my job well. In real life I wouldn’t go back, but in my dreams I’m always overjoyed. I wake up happy and optimistic. Some version of that dream comes to me at least once a year, I suppose. Sometimes several times. Dreams are mysterious. They’re telling us something, but they’re coy about exactly what. That’s what made last night’s dream so bad. There was no ambiguity. This was pure, unadulterated self doubt in the room with me and it gave me no quarter. I got up and continued work on the revisions anyway. Who’s afraid of omens?