We’re all tightly packed together here on the internet. Social media is a fuzzy category and now includes such platforms as LinkedIn, which I think of mainly as a place to hang your shingle while looking for a job. I chose, many years ago, to make myself available online. This sometimes leads to a strange familiarity. It isn’t unusual for me to have an author hopeful to contact me through my personal email or through LinkedIn, especially, to try to push their project. (Such people have not read this blog deeply.) One thing acquisitions editors crave most highly is professionalism. Being accosted on LinkedIn, or in your personal email, is not the way to win an editor’s favor. Some of us have lives outside of work. Some of us write books of our own and don’t blast them out to all of our contacts on LinkedIn. Professionalism.

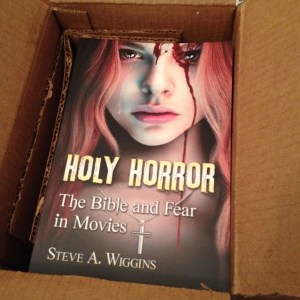

It’s tough, I know. You want to promote your book. (I certainly do.) It seems strange to say that blogging is old-fashioned, but it is. (Things change so fast around here.) But you could start a blog. Or better yet, a podcast. Or a YouTube channel. You can blast all you want through X, Bluesky, Facebook, Tumblr, or Instagram. I admit to being old fashioned, but LinkedIn is for professional networking, not doing quotidian business. It may surprise some denizens of this web world that some publishers don’t permit official business through social media. Email (I know, the dark ages!) is still the medium preferred. Work email, not personal accounts. Some authors (believe it or not) still try to snail mail things in. Publishing is odd in that many people, and I count my younger self among them, suppose you can just do it without learning how it works. Most editors, I suspect, would be glad to say a word or two about professionalism.

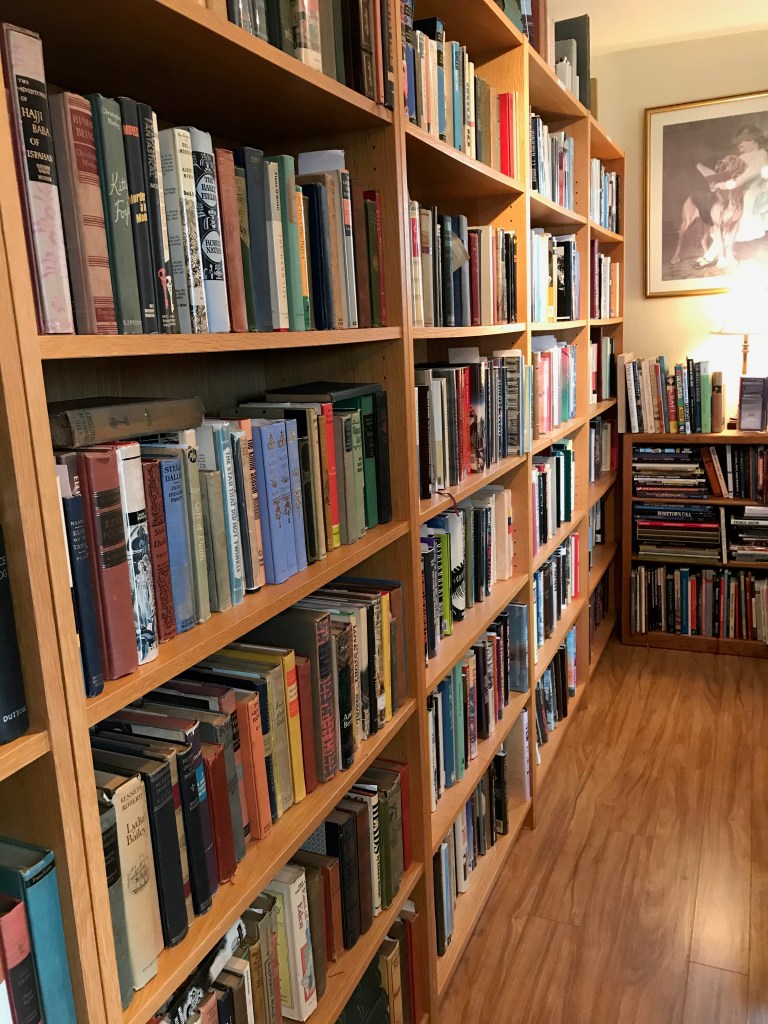

Professionalism is what makes a commute to the office on a crowded NYC subway train possible. We all know what’s permissible in this crowded situation. We know to wait until someone checks in at work before asking them about a project we have in mind. (If you’re friends with an editor that’s different, but you need to get to know us first.) When I started this blog I was “making a living” as an adjunct professor. I was hanging out my shingle. I also started a LinkedIn account. Then I started writing nonfiction books again. Since those days I’ve been trying to figure out the best way to promote them. Professionally done, if at all possible.