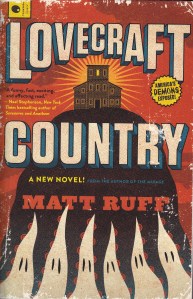

You can sort of tell when an author has a background in religion. Early on in my blog writing, I made note when novels had religious elements. It’s so common that I seldom do that anymore. Matt Ruff’s father was a minister. His understanding of the religious landscape comes through in The Mirage. It wasn’t on my reading list, but someone gave me a copy and the story drew me in. In case, like me, you only know Ruff from Lovecraft Country, this tale’s quite different. There may be some spoilers here, so if you’re thinking of reading it fresh, you’ve been warned!

You can sort of tell when an author has a background in religion. Early on in my blog writing, I made note when novels had religious elements. It’s so common that I seldom do that anymore. Matt Ruff’s father was a minister. His understanding of the religious landscape comes through in The Mirage. It wasn’t on my reading list, but someone gave me a copy and the story drew me in. In case, like me, you only know Ruff from Lovecraft Country, this tale’s quite different. There may be some spoilers here, so if you’re thinking of reading it fresh, you’ve been warned!

Set in an alternate reality in which the superpower in the world is the United Arab States, the story follows three police agents of Homeland Security as they uncover a perhaps unwelcome truth: the world they know is a mirage. It is, in fact, the work of a jinn. Before commenting on that, I would say that you don’t learn about the jinn until a good way into the story. Up to that point I’d call this simply literary fiction. The jinn adds a speculative element to it, and also explains, mostly, how things ended up the way they did. Jinns, by the way, are often considered demons in Arabic culture. They are quite different from Christian demons, and that point makes itself clear as the story unfolds. Our three protagonists begin to uncover hints that the twin towers didn’t actually stand in Baghdad, and that Christian terrorists didn’t fly planes into them on November 9 (11/9). They have run-ins with Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden as warring factions vie for power in the UAS.

This is a great story for trying to understand the world from the point of view of a different religion (unless you’re Muslim). This is a world where Christians are terrorists (you get to meet David Koresh as well) and the United States is a backward country divided over religion. Reading this as events unfolded in Washington, DC last week was a little bit disconcerting. Alternative realities are often just a heartbeat away. The plot is a bit complex at points, but it’s a fairly quick, if profound read. Religion is the heart and soul of this book. That religion could be either Islam or Christianity. Perhaps even something different. The way it plays out is very much like real life, dividing people against each other until reality becomes difficult to bear. For anyone interested in what a Muslim-run world might have looked like, this is a good starting place.