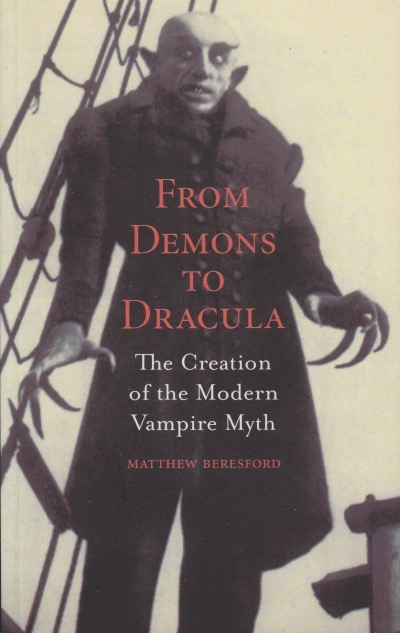

Any book on vampires has to be limited. I first read Matthew Beresford’s From Demons to Dracula: The Creation of the Modern Vampire Myth back in 2009. It has lots of information, but it was long enough ago that much of what I’d learned had grown fusty with age. I began re-reading it as Halloween approached, and am glad I did. The thing about vampires, however, is that you do have to compare sources. Like many explorations of the vampire, Beresford’s notes that there are ancient analogues, but nothing precisely like we think of vampires today. From my own perspective, I tend to think that our modern vampires, like our demons, come from movies. Starting with F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, but more clearly from Tod Browning’s Dracula, our idea of what vampires are have been mediated by the silver screen.

This book ranges widely across time, region, and genre. It discusses early reports that clearly considered vampires an actual threat, as well as movies made purely for entertainment. One thing that I noticed this time around is that the author, being British, seems not to have noticed the tremendous influence Dark Shadows had on the popularity of vampires prior to Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. I suspect that soap operas were not widely known internationally, and even if they were, they were likely not taken too seriously. Dark Shadows was different, however, and it made vampires chic in a way they simply weren’t before the early seventies. At least in the United States, Barnabas Collins helped define the vampire.

Beresford makes the point that there is no single defining characteristic that applies to all vampires. Early European vampires didn’t necessarily drink blood—they were revenants (they’d returned from the dead) but they weren’t always after blood. In the nineteenth century bloodlust became the defining feature of vampires. There are historical points on which to quibble with the argument here, but overall this book is a good overview of how ideas like vampires have been around for quite some time. As someone who specialized in ancient literature for a good part of my life, I would not have called the various ancient analogues pointed out “vampires.” Beresford is making the case that they lay the groundwork for what later became vampires. And Vlad Tepes of Wallachia played his part as well. As did the ancient Greeks. It seems to me there’s more rich ground to explore here and this book provides a very good starting place.