I write a lot about holidays. One of the reasons is that even long before capitalism, societies took breaks right in the middle of things. One of the major seasons of celebration was the vernal equinox. Easter is tied to Passover, of course, but since nobody knows the year of Jesus’ crucifixion the actual date can’t be determined. Passover is a moveable feast and since the lunar calendar is essential in setting Passover’s date, Easter is calculated as being the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox. There has been talk of the three major branches of Christianity—Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant—agreeing on a set date for Easter but even if that happened there would be splinter groups who liked it the old way and the confusion would only grow.

Since astronomical observation has grown so mathematical, the date of Easter can be calculated far into the future. We know just when the vernal equinox will occur, and we know when the full moon will come around. All that’s needed is some calendars and a whole lot of patience (and maybe a calculator). Despite society’s obvious preference for Christmas, Easter has its own array of attendant holidays for some Christians. (Not all Christians celebrate Easter.) For instance, for some today is Maundy Thursday. Tomorrow most will recognize as Good Friday. Nobody’s quite sure what to call Saturday, and many Christians will begin to celebrate Easter at midnight even before Sunday wakes up. Easter does last more than a single day, in some traditions, but it’s not quite as developed as the twelve days of Christmas.

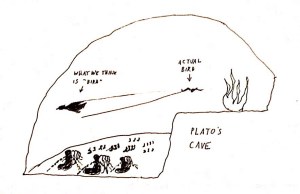

Lately I’ve been considering that how these holy days are sacred for some and secular for others. One of the realizations that globalization has wrought is that not everybody shares the same concepts of how universal events—such as the vernal equinox—should be commemorated. Although on the equator every day’s not quite an equinox due to the earth’s tilt, it isn’t as dramatic as the changes that occur in temperate zones. Christianity was custom-built for European holidays, which is what it tends to keep. The history of the holidays is more complex than it might seem at first. Add to that widespread disagreement around the world as to both religion and to when certain events should be calculated and you’ll need more than a slide-rule to figure it out. So as we begin the Catholic and Protestant Easter season (Orthodox Easter is about a month away yet), it may be helpful to remind ourselves that what day it is might just be a matter of perspective.