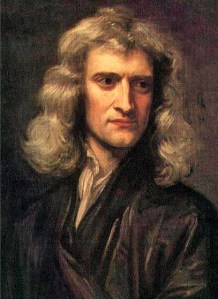

Please don’t read too much into this! I read a lot of professors who spend their careers trying to understand a previous scholar’s thoughts. I suspect this happens quite a lot in philosophy, but it fits pretty well in religious studies also. And I wonder, what of those intellectuals where were grappling with pure ideas? Did they know they’d become adjectival? In other words, did Immanuel Kant know that he was Kantian? Or was he just writing stuff, trying to explain how he understood being in the world? Now scholars dedicate themselves to understanding Kant. Or in more recent times, Derrida, Lacan, and Bakhtin, or whoever’s the flavor of the day. The ones who were too busy being Derrida, Lacan, and Bakhtin to figure out what someone else was saying about things just wrote.

I often wonder about how higher education has shifted the way we do scholarship. It’s not really a place to test out ideas that the world can evaluate, but more a place where specialists can discuss possibilities and what someone else might’ve thought of something. I guess that’s why I tend to think of my last four books as being non-academic. I’m not using the tired formula of reacting against what some theorist has said about my subject. I’m simply observing and drawing inferences. Maybe it’s because I wasn’t raised in an academic environment. I remember reading Nietzsche for the first time. How he didn’t footnote. How he didn’t argue against what some prominent others had said. He simply wrote. And he did so brilliantly.

Perhaps it’s yet another example of having been born early enough. Tech has made it remarkably easy (for those without families to feed) to become writers. No agent or editor required. And things like Book-Tok can make those who publish outside the Big Five famous. What would Kant have done? That’s a nice Kantian question. In fact, the whole reason I began this post was that I’d run across James C. Taylor’s A New Porcine History of Philosophy and Religion on my shelves. Just seeing it reminded me of the Kantian pig refusing to lie to an axe-wielding maniac. That got me to thinking of Kant and what it must’ve been like to see him being Kantian. I’m no expert. I took a lot of courses in philosophy and religion back in the day, but I have a book about philosophical/religious pigs on my shelf. Somehow I suspect Kant wouldn’t have appreciated his page in this book, even though it gave me philosophical thoughts to start the day.