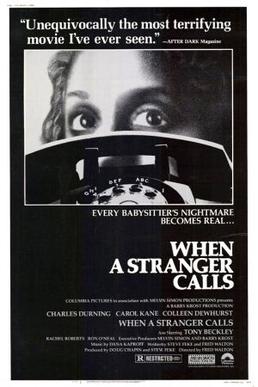

The first twenty minutes are impossibly scary. I didn’t see When A Stranger Calls back in 1979, when it came out. I prefer my monsters in non-human form, thank you. But still, to be writing books on horror movies without ever seeing what is widely regarded as being the scariest opening ever? Although the first twenty minutes were indeed scary, and extremely tense, for me the scariest part came after that because I didn’t have any idea what else would happen. Of course I knew the initial calls were coming from inside the house. That urban legend seems to have been around since I was a kid. I wasn’t sure who survived, if anyone. And psychopaths are scary in real life, let alone in fiction where they can break into locked houses pretty easily.

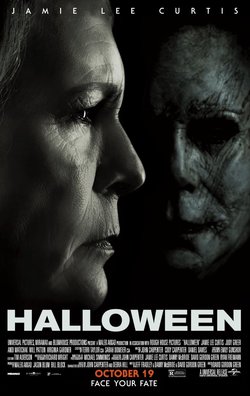

The story, as laid out, is better than most critics give it credit for being. The only part that seemed difficult to believe (and don’t get me wrong—I love Charles Durning) was that an overweight John Clifford could do all that running (particularly up stairs). It’s believable that the criminally insane can escape—Michael Myers seems to do it every couple of years—and even that they could blend in on the streets of any city. I do have to agree with the critics that the writing isn’t great, but those who say it’s not scary enough, well, they’re made of sterner stuff than me. Or perhaps they lack empathy, which is a scary thing in itself.

Curt Duncan, perhaps because he’s clearly killed at the end of the movie, never became the serial boogyman that the aforementioned Myers, or Jason Voorhees, or Freddy Kruger, or Hannibal Lecter became. Although sequels were made, once you’ve seen that first twenty minutes of Stranger, you get the sense that they’re not going to be able to do it any better. Snopes tells us the legend began in the sixties. It was clearly a reaction to the proliferation of telephones and the potential to abuse such technology. That’s an object lesson we still haven’t learned. We now seem never to be more than inches away from a device at all times. Except maybe when in the shower, but that’s a scary story for another time. Although I won’t be going back to rewatch or analyze this one over and over, still I feel I somehow earned a stripe or bar for watching it. And I now feel even more appreciative of caller ID.