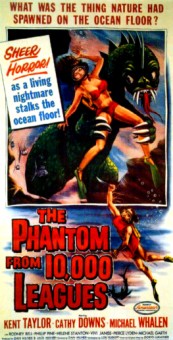

Much of movie viewing life is about making connections. Many, many films have been made and I’m not the first to suggest that cinema is a form of modern mythology. But those connections! Pressed for time one busy weekend, I found the brief, low-budget The Phantom from 10,000 Leagues. It was included with Amazon Prime and I had an obligation in about 90 minutes. I could just squeeze it in. As I’d anticipated, it was another of those poorly written, cheeky teen-magnets from the fifties. The monster created by radiation, the threat to the world that the government sends only two guys to handle, and lots of lingering shots of men in business suits walking on the beach, it’s about what you’d expect. It did well at the 1955 box office, though.

My first thought was that it was an attempted marriage between The Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. Indeed, Black Lagoon had been released the year before, opening the realm of underwater filming for monster movies. It, however, had a believable monster that wasn’t so monstrous. The “phantom”—the name is never explained—is obviously a person in a cheap monster suit that can barely open its mouth. It kills by holding people under water, or getting them into a radioactive beam, or preventing them from getting away from dynamite. Oops, that last one’s a spoiler, I guess. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms came out a year before Black Lagoon. The title of The Phantom from 10,000 Leagues title was obviously ripped off from it, and the atomic connection and undersea beast are common to both. Connections.

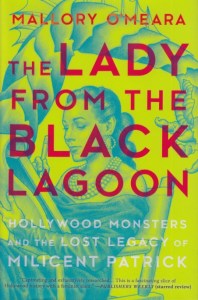

The Beast had the benefit of a monster by the master, Ray Harryhausen. And it was based on a story by Ray Bradbury. That was a winning combination. The Phantom claims to be based on a story by Dorys Lukather. This movie is all she’s known for writing, God rest her soul. Produced by the subtly named American Releasing Corporation, the production company would go on to become the respectable American International Pictures. Interestingly, given the sexism of the era—reflected fairly clearly in the writing—the monster was played by a woman. Norma Hanson, like Milicent Patrick, brought a monster to life only to be largely forgotten. Patrick was rediscovered by Mallory O’Meara, but Hanson—one time a diving world-record holder—seems to have faded. Had I but more time, I would enjoy diving those 10,000 leagues to bring another forgotten Hollywood monster woman to life. And if I had the connections.