Every now and again, the great cosmic spheres align in their eternal turning and something just right clicks into place on our little planet. Such a juxtaposition must have recently occurred, for just when my worry about dragons had been reaching a crescendo, I received an offer for “dragon bane,” a beautifully crafted double-axe in the Minoan tradition, for only $39.99. The double-axe, or labrys, actually predates the Minoans, probably originating in ancient Sumer. The dragon predates even that.

I’ve posted on the origin of dragons before, but of all mythological creatures dragons are perhaps the most tenacious. In various guises they reappear when we thought that they were gone. They are among the most ancient of feared creatures. Representing the untamed, indeed untamable areas of life, the dragon is the perfect symbol of chaos. Dragons are the disorder against which gods always struggle. Metaphorical dragons are always more troublesome than physical ones.

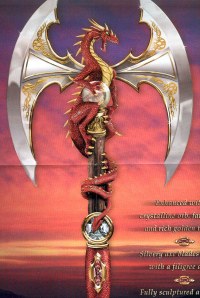

Although the idea of being a sword-swinging hero out to vanquish the forces of evil is an appealing one, I know that I won’t be purchasing this collectable. I have too much respect for dragons to see them slain by gods or mortals. What would life be without our dragons?