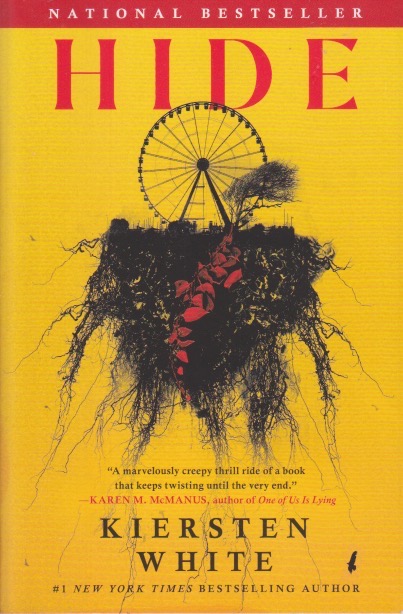

I’m afraid there may be spoilers—but not for the ending—below. Discussing this story will be difficult without giving some things away. Kiersten White’s Hide has given us an imaginative world with masterful misdirection. Fourteen people a bit down on their luck, and strangers to each other, are offered an opportunity to win $50,000. They have to hide in an abandoned amusement park for a week where two of them will be caught each day and the last person remaining wins. The novel mostly follows Mack, a woman whose father killed her family while she survived by hiding. Not only does she have survivor’s guilt, but she’s been homeless and the shelter director thinks she’ll have a chance at winning the prize. There is a lot of social commentary here, as well as a monster. Okay, spoilers below.

The minotaur is a most useful monster. The backstory here isn’t in Greece (well, the deep backstory is, but that is only played out partially here) but in Asterion. No state is given for the town, and the contestants can’t be given that information. They’re locked in the park, with supplies, but very little information. Then the contest starts. After a couple of days Mack and a couple others begin to suspect that something’s wrong. Those who get caught while they’re hiding leave personal effects behind, and since they all need the money that seems unlikely. Then their host stops coming, leaving the bewildered contestants on their own. Mack and those she’s befriended come to understand that being “out” is really being eaten by the minotaur. Well, they don’t realize it’s the minotaur. The one who does gets eaten before he can tell.

In any case, this is a tense horror story based on a classic tale. There is, of course, a rationale for the murderous behavior in a modern setting. White keeps you waiting quite a while to learn what it is, and there are plenty of places where I thought I’d figured out how it’d end only to be proven wrong. And she gives believable character sketches and explores the kinds of motivations that drive different people who find themselves needing an income. (One of the characters was raised in a religious cult—bonus!) Those who are poor aren’t always at fault, but those who are wealthy will do anything to preserve their excess. We see that playing out in daily life, even as it’s being explored in fiction. The minotaur isn’t always what we think it is. And the more you think about its insidious origin story provided here, the scarier it becomes.