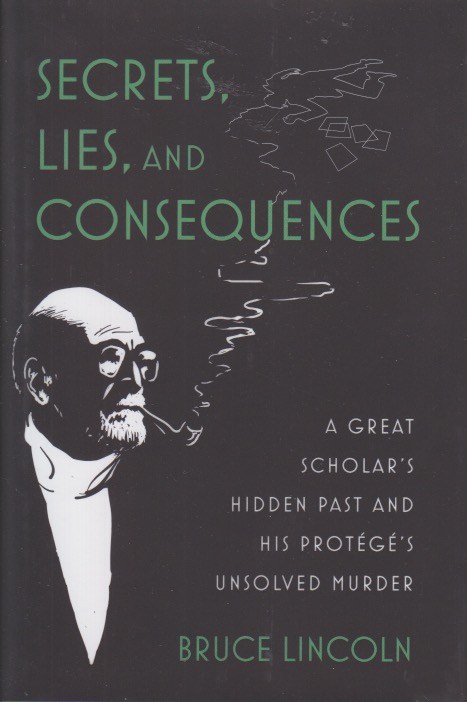

Strange as it may seem, the world of academic religious studies can have high drama. On May 21, 1991, Ioan Petru Culianu, a professor of religion at the University of Chicago, was followed into a men’s room and shot through the head. The murder was never solved. Culianu was protégé and, many thought, successor to Mircea Eliade, perhaps the most famous religion professor of the last century. Eliade was a Romanian American, and in his youth supported a fascist political movement, his connection with which he later covered up. A bit of necessary background: the University of Chicago is a powerhouse school of religious studies. Its graduates are nearly as influential as those of Harvard. And Eliade trained many of them. Including Bruce Lincoln. Secrets, Lies, and Consequences is a fascinating book, even if it gets into the weeds. You’ll learn a lot about early twentieth-century Romania if you read it.

Like many Chicago grads, Lincoln has had a distinguished career. Even though I worked in different areas of religious studies than he does, I knew his name. I read this book because it is full of intrigue, but also because, until I heard of it, I’d never known anything about Culianu or his unsolved murder. A scholar’s scholar, Lincoln taught himself Romanian to be able to write this book. (This is what I miss about being a professor, the freedom to undertake such Herculean tasks and have it be considered “normal” on-the-job behavior.) The end result is a brief, complex, and wonderful book. This isn’t a proper whodunit, though, and although Lincoln has some suspicions about what might’ve happened to Culianu, there is no smoking gun. His murder took place while I was a doctoral student in Edinburgh, whence, as far as I could tell, the news never reached.

Eliade was a towering figure. He wanted to put Romania on the intellectual map and he succeeded. His work is still studied and analyzed. He wrote novels as well as monographs, and some of his ideas have become standard fare in religious studies. Few figures in the discipline cast a longer shadow. I was in seminary when he died, but some of his works were recommended reading by that time. This little book got me thinking about at least two big things: how some people become academic superstars, and how cancel culture sometimes brings them under the microscope. Humans are raised in a culture and sometimes our young ideas, not fully formed, come to define our entire biological trajectory on this planet. And sometimes we have regrets. This is a fascinating study of one such case.