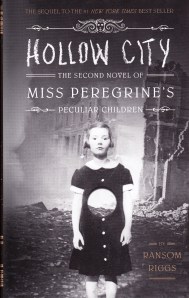

There’s a kind of trinitarian logic to the trilogy format. Long before Hegel’s model of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, people have grouped things into threes. And there is a hook that film-makers have used to ensure that viewers will come back for the third installment: the cliffhanger. The second episode leaves everything unresolved and you’ll be sure to see the third. Think of the original Star Wars trilogy, or Back to the Future, or even Pirates of the Caribbean. In each case the first film could stand alone, but the second insisted on a third. This is a little trickier with books since, as we all know, publishing is a slow business and writing takes time. I saw Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, by Ransom Riggs, in 2011. I knew I would read it since the cover alone was so intriguing. Young adult literature, it turns out, has come a long way since I was able to classify myself that way. Then Hollow City came out. It ended as a cliff hanger (remember the formula), back in 2014. Just over a year and a half later, The Library of Souls was released.

There’s a kind of trinitarian logic to the trilogy format. Long before Hegel’s model of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, people have grouped things into threes. And there is a hook that film-makers have used to ensure that viewers will come back for the third installment: the cliffhanger. The second episode leaves everything unresolved and you’ll be sure to see the third. Think of the original Star Wars trilogy, or Back to the Future, or even Pirates of the Caribbean. In each case the first film could stand alone, but the second insisted on a third. This is a little trickier with books since, as we all know, publishing is a slow business and writing takes time. I saw Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, by Ransom Riggs, in 2011. I knew I would read it since the cover alone was so intriguing. Young adult literature, it turns out, has come a long way since I was able to classify myself that way. Then Hollow City came out. It ended as a cliff hanger (remember the formula), back in 2014. Just over a year and a half later, The Library of Souls was released.

Having just finished the trilogy, reading each as it came out, I would say that, like most trilogies, the first installment was the best. Freshest, a new idea, where characters exist with whom the reader participates by in filling in the blanks, a series grows more complex as it expands. Some elements that weren’t there at the beginning have to be read back into the previous installments. In my case, I’ve read so many books in the interim that some of the details have grown hazy due to the simple passage of time. Still, Riggs is to be highly commended for bringing souls back into discourse among the young. Too long we’ve been sold the story that we have no souls.

I’m not going to go into any great detail here since those who want to learn how Riggs handles the tale will read his books, but I will say that a stubborn materialism has settled over intellectual culture. Some neuroscientists have naively said, “we’ve looked for it and can’t find it, therefore it must not exist.” And since most of us don’t have access to their kinds of equipment or training, we’re told to acquiesce. Give up your souls—buy into materialism. Buy stuff. That’s what we’re all about. It is a relief, in the midst of all of this, to have a popular writer suggesting, through fiction, that it is souls that make us who we are. The books aren’t preachy. Indeed, it would be difficult to say they are religious in any conventional sense. They are, however, soulful. And for that I am very glad to have read them, even as a middle-aged adult.