Where do books come from? It still comes as a surprise to many authors, but books tend to be shipped by, well, ship. When publishers use overseas facilities, it’s far too expensive to send books across the ocean by air. I had many people express disbelief when I explained their books were delayed by the Suez Canal blockage, but if most of the world’s international goods are sent by ship (and they are) what might seem like a quirky news story has very real ramifications worldwide. I was reminded of this by a recent NPR story of two new cookbooks having been lost at sea. The ship from Taiwan, bound for New York, ran afoul of a storm in the Azores, resulting in the loss of 60 shipping containers—including those holding the newly printed books. There is a worldwide shortage of shipping containers (seriously) and one of the problems is they keep falling off ships.

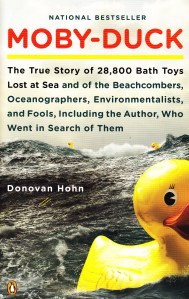

If you haven’t googled “cargo ships” and looked at the image options, do. You’ll see astonishingly large ships with what look to be entire cities worth of cargo containers stacked on the deck. Many of these containers are lost at sea. Current estimates are that about 1,000 containers fall off of ships per year. Although the authors of these particular cookbooks took a lighthearted approach to the news, the book that really brought this home to me was Moby-Duck, which I blogged about some years back (you can read it here). That book was about trying to follow the plastic “rubber duckies” that fell off a ship back in 1992. This isn’t, in other words, a new problem.

Videos posted of these massive ships being tossed about and losing cargo are impressive in their own right—they make the ocean seem omnipotent. But the fact is, we’ve littered it pretty badly. Books, in their defense, will decompose naturally. We live in a society defined by consumerism. We see things and we want them. In order to make them inexpensive, American companies buy the items from overseas where labor costs are much cheaper (and where many nations have socialized medicine, I might add, making employees cheaper to pay). As ships grow larger we might expect these kinds of accidents to increase. The older I get, the more I pay attention to economics. The dismal science does hold a macabre fascination, especially when entire printings of a new book end up at the bottom of the ocean. Authors, if they’re curious, ought to consider where books come from.