Adulthood is where you begin to recognize the folly of growing up. Like most people, when I “matured” I was ashamed of things I made as a child and, regretfully, threw them away. This came back to me recently as I was thinking of a sketchbook—actually a scrapbook that I repurposed in my tween years. I love to draw. I don’t do it as much now as I’d like (thanks, work!), but I was encouraged in it by art teachers throughout school who thought I had a little talent. The sketchbook, however, was only ever shown to my brothers, but mostly only looked at by me. This particular project was where I was making up monsters. As with my writing, I’d never taken any drawing classes, but I had an active (some say overactive) imagination. (That’s still true.)

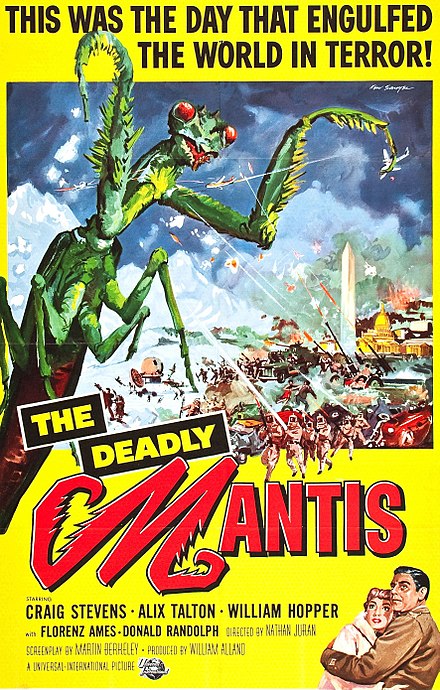

In any case, a discussion with my daughter brought back memories of this book I’d discarded by the time I went to college. I still remember some members of the menagerie I’d concocted. Even now that I’ve seen hundreds of monster movies, most of those I’d fabricated as a child have no peers that I’ve seen. These weren’t monsters to be incorporated into stories—they were purely visual. Although, I can say that my first attempted novel (probably around the age of 15) was about a monster. I got away with being interested in monsters in high school, but college was a wholesale attempt to eradicate them. Even so my best friend from my freshman year (who left after only a semester) and I made up a monster that lived in the library.

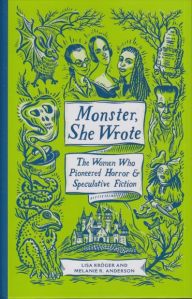

As an academic, until very recent years, monsters were off limits. If you wanted to be sidelined (and in my case it turns out that it wouldn’t have mattered) you could explore such outré subjects. Now it turns out that you can get mainstream media attention if you do (as a professor, but not, it seems, as an editor). I’m sitting here looking back over half-a-century of inventing monsters, with a sizable gap in the middle. The interest was always there, even as I strove to be a good undergrad, seminarian, and graduate student. Now I can say openly that monsters make me happy. I can also say, wistfully, that I’d been mature enough to keep that sketchbook that preserved a part of my young imagination. It was tossed away along with the superhero cartoons I used to draw. And the illustrations of favorite songs, before music videos were a thing. Growing up is overrated.