The Tank is a reasonably well done monster movie. It isn’t great, but monsters are monsters and they can be appreciated in their own right. The main problem of the movie is that it’s not terribly well written. The premise is scary enough. A family of three goea to inspect a property they inherited but which nobody in the previous generation had ever mentioned. The house is in a remote cove on the Pacific, in rural Oregon. They arrive to find it boarded up and in poor repair. Ben, the father, begins making basic repairs while his wife Jules and daughter Reia try not to become too creeped out. The water supply comes from an underground, eponymous tank that brings spring water into a reservoir. There’s no electricity. That night something tries to get into the house. Ben assures his family it’s only a raccoon or some other woodland animal.

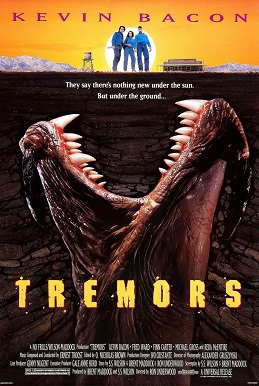

The tank, where the monster comes from, is certainly creepy in its own regard. When they become convinced something may indeed be wrong with the property a realtor shows up with a generous offer from a buyer. She is, unfortunately and predictably killed as she tries to leave and we see the monster for the first time. This is a dilemma for all monster movie makers—when and how much of the monster to show. We’ve seen monsters of every description and seeing a new one invites comparison with others. This monster, a toothed amphibian, troglomorphic from having evolved in a deep cave, has some resemblance to the Demogorgon from Stranger Things. It attacks by sound (A Quiet Place) and perhaps simply by sensing movement. There are a lot of “why?” moments in the film; why didn’t they do this or that obvious choice of action. But still, there’s a new monster.

Eventually Ben is able to contact police but the police officer (why did he not pull his gun when he first saw the monster?) is killed. All three members of the family are attacked with Jules ultimately getting them to safety. Part of what makes this a mediocre offering is that there is nothing profound about it. The monster was released—actually it’s a family of monsters—when the tank cut into its sealed cave. It attacks people, it’s implied, the way an axolotl defends its territory. This isn’t explored in any detail. There’s also the backstory of Ben’s family; his father and older sister were killed by the monsters, but his mother was deemed insane and responsible for the deaths. So there’s a lot going on in the movie but no real resolution to the many ideas that are started by the story. It’s a meh horror movie, but it does have a monster.