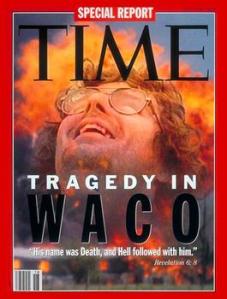

It seems that the world has lost another messiah. Sun Myung Moon, founder and leader of the Unification Church, died yesterday in South Korea. When I was younger “the Moonies” were known as a cult, but scholars of religion have abandoned both terms (Moonies and cult) as pejorative ways of referring to alternative religious beliefs. Monotheistic religions tend to be, by their nature, supersessionistic. They claim that they are the final revelation, but then as the world ages new religions appear and those of more time-honored traditions wonder how to define the new-comers. Accompanying the speed of technological development, religious developments keep apace. Now we are so accustomed to a world full of religions and most people are ill-equipped to tell the difference. Other than the highly public mass marriages, what can the average non-Unificationist tell you about the religion?

This dynamic illustrates a basic fact of human beings—we are meaning-seeking creatures. Founders of New Religious Movements, often convinced that they have something valuable to offer, seldom have difficulty locating followers. We are not trained to think for ourselves in religious matters; in fact, most religions would prefer to have unquestioning followers. Not based on the same logic as physics or mathematics, religions are easily backed into the “it’s a mystery” corner when logic breaks down. That is not to suggest that logic is the only way to know the world, but it does mean that the choice of correct religion often comes down to a feeling, an emotional satisfaction. Problems frequently arise when practitioners of a religion mistake it for science (or when a religion itself makes that mistake).

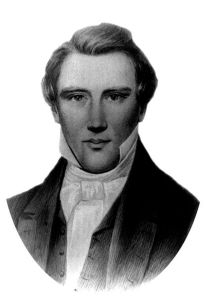

Over time the New Religious Movements that survive become benign elements of the religious landscape. Although many Americans are still scratching their heads about what exactly Mormons are, they are certainly nothing new or unusual. As a religion the Latter Day Saints are less than two centuries old, but since many people have trouble distinguishing a Baptist from a Presbyterian (on a theological level—the political spectrum is fully represented in both traditions) and could tell you very little about when either tradition began, what do they know of Joseph Smith’s followers? We are far too busy to spend time researching religion. Most people stay with the one they’re born into, and every few years a new one makes it onto the radar of public awareness. The Unification Church, which has at least five million members, may or may not survive the death of its messiah. Either way, there will be plenty of new options for anyone shopping around for a new faith.