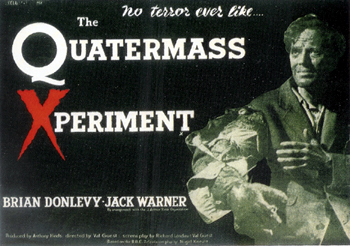

Hammer films are coy. In these days of digital rights management, they’re often difficult to locate in the United States. Even on streaming services. I’d known about Quatermass since I was a kid. I’d heard about Quatermass and the Pit as a pretty scary early science fiction-horror offering. I’ve still never seen it. Quatermass was a BBC television character, a kind of mad scientist figure. The Quatermass Xperiment was the first of a set of four Hammer films based on him. Also known as The Creeping Unknown, it was cast with an American Quatermass (ironically, it turns out) to appeal to American viewers (who can now seldom access the film). In any case, one of the streaming services finally acquired rights to the 1955 movie. The special effects were naturally primitive, but that doesn’t stop this from becoming a scary film.

Watching these early movies is like studying history. Other films were influenced by The Quatermass Xperiment, most notably Lifeforce. I couldn’t help but think of Night of the Living Dead as well. Quatermass, a rogue scientist, sends a rocket into space with three astronauts. Since this was before we had any kind of conception of how this might actually be done, the idea seems implausible, of course. The rocket returns with only one of the three crew members, and he’s morphing into something else. Despite his arrogance, Quatermass realizes he has to cooperate with the police to contain the menace. Inspector Lomax describes himself as a “Bible man,” unacquainted with science, and Quatermass considers his work superior to that or mere police. When the hybrid is finally located and destroyed, however, it is in Westminster Abbey.

Although the runtime is just over an hour and some of the acting is quite wooden, this is an affecting story. The scene where the transforming man encounters the little girl’s tea party bears elements of the pathos of Frankenstein. Without the budget, science, and even acting resources of modern productions, The Quatermass Xperiment manages to fall squarely into horror with a monster I’d been waiting since childhood to see. In those days you were at the mercy of your local television offerings. Now that we have worldwide content on the worldwide web, we still restrict viewing so that the most money can be made from a movie that’s seven decades old, and its cohort. In any case, this experiment has left me determined to find what Quatermass discovers in the pit. Once that becomes available on a service I use.