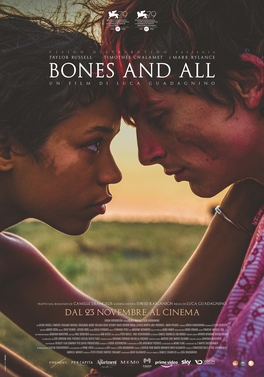

Horror is getting harder and harder to define. Maybe it’s because movies are venturing further and further into mixed genres. The best genre I’ve seen suggested for Bones and All is “romance horror.” It is a most unusual love story with a tinge of the supernatural to it. Maren has an unusual problem. She eats people. This started when she was three and her father, when she turns 18, sets her out on her own. Another “eater,” Sully, finds her by smell, teaching her that eaters can identify each other that way. Sully begins to creep her out, so Maren heads west to try to discover her mother. She sniffs out another eater, Lee. Not sure he wants to get mixed up with another person with his issues, he nevertheless allows her to come along. They travel from Kentucky, through Missouri and Iowa, to Minnesota. Along the way other eaters find them, by smell.

In Minnesota, Maren finds her mother in an institution and learns that her mother was also an eater. Eventually Lee confesses that his father was an eater. Sully, who’s mentally unstable (for an eater) has been following Maren and decides he has to kill her for what she knows. Lee rescues her, but is critically injured in the process and insists that Maren eat him. Now, from that description you might think this is either a comedy or a film with horror score and stingers, but it’s neither. It’s a straightforward romance, following two lovers with a unique problem. Only it’s not as unique as all that since there seem to be quite a few cannibals around. The theme, and the feeding scenes, are definitely horror. But is this a horror movie?

Although Maren and Lee are moral people, and likable, they are the monsters in this film. While they try not to kill, they are driven to eat other people and they do resort to violence to do so. The signature accoutrement for horror are absent as the focus remains steadily on the building romantic relationship. You want Maren and Lee to succeed because they’re nice people. But they are monsters according to definition. Often in horror serial killers and other humans may serve the monster role in the absence of supernatural, or preternatural creatures. There’s an almost vampire-film feeling to this story (the heightened senses, and all that blood) but eaters aren’t constrained by daylight or crucifixes. It’s the kind of movie that keeps asking the question “What am I?” and leaves the viewer to try to digest a definition.