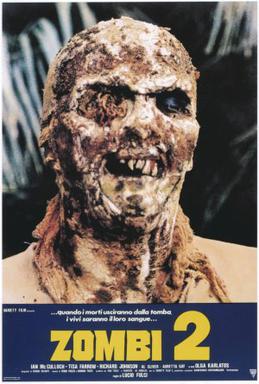

The first thing to note about Zombi 2 is that there’s no Zombi 1. Except that in Italy George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead was released under the title Zombi. And Zombi 2 is also called Zombie. It’s kind of a 1970s classic, but instead of a spaghetti western, it’s an Italian movie filmed in America. This is one of those movies that has grown in reputation over the years and when revisited by critics is considered better than it was initially assessed. All that discussion of the title clued you in that it’s about zombies, but what, specifically? Well, it does take the concept back to its Caribbean roots. A woman accompanied by a reporter, is trying to learn what happened to her father on the mysterious island of Matul. Another couple who own a yacht reluctantly agree to take them to the island.

Meanwhile Matul is increasingly facing reanimated dead (one of whom escaped to New York City). The local doctor can’t accept that voodoo is actually involved and has stubbornly remained to try to find the “actual” cause. The two couples from the yacht learn from the doctor that the woman’s father had become a zombie. The doctor knows to shoot zombies in the head, but the new-comers haven’t quite figured that out yet. The zombie infection is passed on by a bite, but anyone who has died can come back. And return they do. They storm the hospital where doctor is trying to hold out. In the end, everyone but the original couple has been bitten or killed, and the zombies have taken over the streets in New York City.

This isn’t bad for a zombie movie, but it’s not up to Romero standards. Of course, few are. I had only recently learned about it from a friend, and it was old enough to be free on a commercial streaming platform. Zombies have some inherent contradictions, of course, and unless they’re handled well they can look a little silly. That’s my overall assessment, not bad but a little silly. Part of the draw of zombie movies is that they deal with inherent contradictions. Bodies that lack the intricate biological structures required for walking, digesting, indeed, for doing what living people do, simply can’t walk around eating people. And yet here we are. George Romero gave the cinematic world the modern zombie, and his superior efforts have led to many attempts at bringing believable undead back to life. If, like me, you overlooked this one, it’s worth catching, especially for free.