Telinema is a strange place. (This is my word for television and cinema, since apparently no such term exists.) My wife and I have been making our way through Twin Peaks. We missed this when it first aired, being somewhat preoccupied living in Scotland. As with most telinema involving David Lynch, there’s quite a lot to ponder. (I’m less familiar with Mark Frost’s oeuvre.) The show only ran for two seasons, but as often happens with substantial short-run shows like this, it became classic in retrospect. Lynch had made movies before, and the initial series was like watching a several-hour film. Then the movie came. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me tells the backstory of what had happened before the series began. Like the X-Files, you kind of need to interlace the movie in with the series. So we have.

Knowing me, I’ll probably write up a reaction after watching the third season, but I want to reflect a little on telinema. Visual media have been around at least since cave drawings were first made and their power recognized. People are captivated by images. When movies started, they were short and sprinkled in with other entertainments until the idea of a feature-length film developed. If you were going to spend an hour or more with a movie, there had to be a story. (Some of those stories, early on, seemed to involve quite a lot of pedestrian activities, of course.) Then television happened. Movies could be shown on TV and movies could be made specifically for TV. Then impressive series, like Twin Peaks, required a theatrical movie to get part of the story across. They became hybrids.

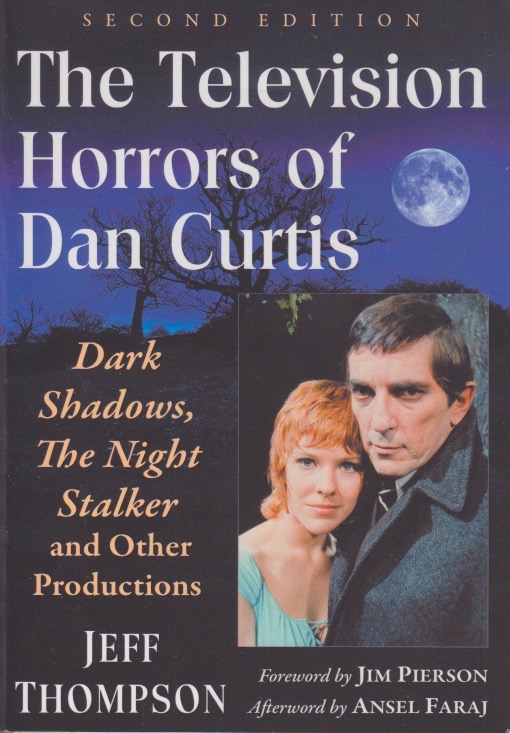

Lately I’ve been realizing just how much “how a story goes” matters. We are story-telling creatures. Our lives are the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. And some of us are obsessed with the true story. What really happened? Telinema sometimes makes this difficult. Dan Curtis, for example, made House of Dark Shadows—a theatrical movie—as a version of what he’d already produced in television land as the daily Dark Shadows. Since there’s no word doing the work telinema does for me, I’m not quite sure how to search to see what the earlier examples might be. The point is a compelling story will draw fans. And being visual creatures we’ll watch if the story interests us. Sometimes we have to watch across “platforms.” Get out of the house into a theater to see how the story goes. Yes, we need a word for this and we need to study just how far we’ll go for a story.