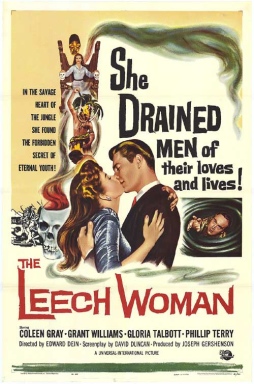

Movies with no likable characters, or none with any redeeming personality traits, are difficult to remain awake through. At least on sleepy weekend afternoons. The Leech Woman is one such movie. It was difficult to get past the premise that an aging woman is cause for alarm among the overly entitled male characters. Dr. Paul Talbot is disgusted by his older wife until he finds credible evidence of a concoction that will cause a person to grow young again. Wanting her to be his experiment, he takes her to Africa where he witnesses the rejuvenating formula in person. It requires, however, a murder to be effective. For her victim, June chooses her husband. The effects, however, are only temporary so June will need to keep on killing to remain young. Each time the formula wears off she’s prematurely aged.

When she’s young again, the men around her feel it is their right to claim her, which, in a sense, provides her with a ready pool of victims. On the other hand, it reflects attitudes beginning to die out as the sixties began. Many of these movies from the fifties throw in a woman to provide little more than love interest. Sometimes these women have a profession—reporter is one that shows up occasionally, or perhaps in a military role or as nurse—but mostly they are there to find a husband and become, ideally, a housewife. Many unrealistic men today still think that should be the case, but few jobs earn enough for the possibility of being a one-income family. Besides, did anyone ever think to ask the women what they wanted?

Aging isn’t the easiest thing to do. This movie plays up the stereotype that men become “distinguished” with age while women don’t. Such unreflective outlooks on aging completely overlook things like aching backs and forgetting things that are typical for just about anyone who makes it past a certain landmark. In fact, aging is something we all face in common, and our attitudes toward it can make all the difference. Fortunately since this movie came out, we’ve had many role models showing us that women do retain their worth and dignity as they age, even as men do. We are an aging population. One benefit, hopefully, to the passing years is the accumulation of wisdom. And that applies, no matter gender or sex. We reach a certain age and we look back and wish we’d known then what we know now. That takes place with generations, too. That way we can say Leech Woman is a period piece, but that still doesn’t make it a good horror movie.