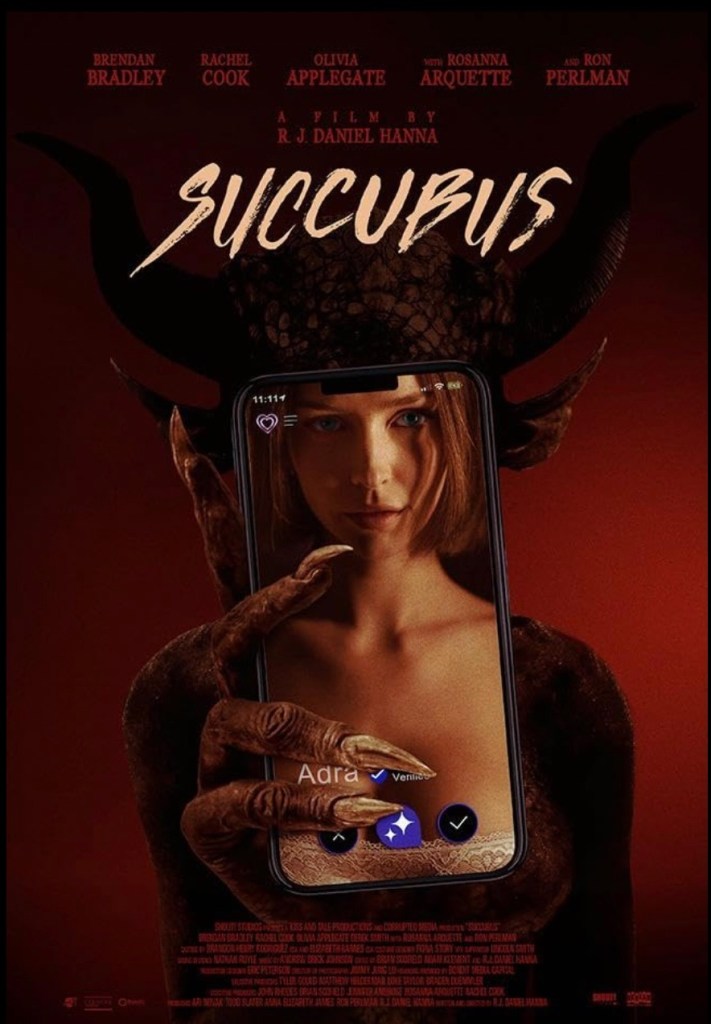

So I was discussing demons with a friend, as you do, and I was looking for a free movie. One that my streaming service recommended was Succubus. There are other movies by this title, so this was the 2024 version. Knowing what a succubus is, traditionally, and having just discussed what demons are with a friend, curiosity overcame me. First of all, I have to say that for a Neo-Luddite like myself, the first half of the movie was a blurry slurry of texts while video chatting while watching the baby monitor that I wondered how people really into the internet get anything done in real life. Sorry, IRL. I’ve had a few people try to initiate chats with me on the few socials I use, but I only respond once a day in the brief window in which I use social media. It just doesn’t appeal to me.

Still, Succubus held a number of triggers for me. But first, a summary. Chris, having a trial separation from his wife, meets Adra, a succubus, on a dating app. She traps him by having him kiss her through the computer and meanwhile kills his best friend who visits her location physically. Meanwhile a physicist, a former victim, is heading to Chris’ house to try to bring him back from limbo, and, failing that, to kill him. The succubus wants a body, of course, and when Chris realizes this, he castrates himself when he and his wife get back together, to prevent the succubus from inhabiting their children. The triggers for me had nothing to do with the demonic aspect, but with the fact that Chris at first is concerned Adra is a scammer. Having fallen for a scam myself, that aspect was scarier than the entire rest of the movie.

As a horror film it kind of works. I’m not really a fan of movies that take place on devices, but about halfway through that part gets dropped. What was of particular interest was only briefly suggested and was worth thinking about. As Chris tries to research the physicist online, he discovers that he’s a researcher in dark matter. The implication, never spelled out, is that dark matter is demonic. This could make an interesting trope, if it hasn’t already been done. Dark matter and dark energy make up a large part of the universe, we’re told. Think about it. It also kind of addresses the question of how spiritual beings make their way into a physical form. Of course, that’s what succubi are all about, isn’t it?

P.S. Sometimes I swear I need a handler. This post was queue up on December 15 but I forgot to click “Publish.” If a day goes by without a post, somebody feel free to poke me…