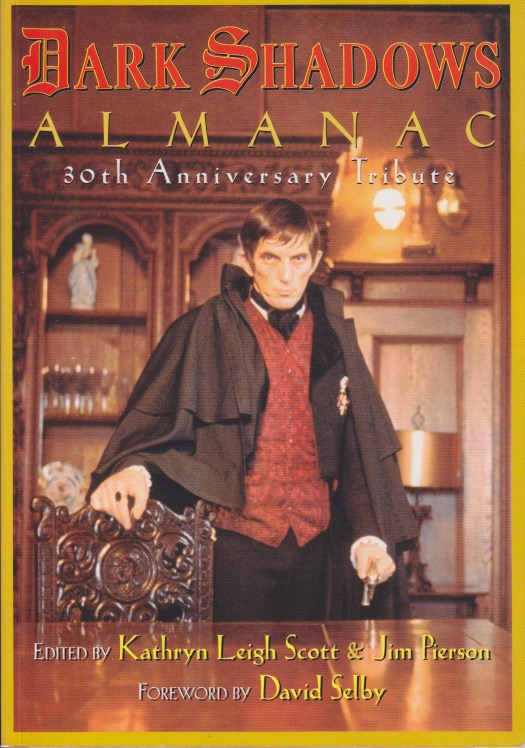

Fandom is a weird thing with me. Having wide-ranging interests, coupled with an at times obsessive personality, my likes are intense but fall short of the kind of fan who purchases everything associated with their fascination. A friend kindly sent me the Dark Shadows Almanac, edited by Kathryn Leigh Scott and Jim Pierson. I try my best to read books friends send me, and working my way through the Almanac, I realized just how far short of real fandom I fall. Dark Shadows was likely my gateway to horror. Watching it after school is one of my early memories. But I was quite young at the time and beyond Barnabas, Quentin, the wonderfully gothic house, and the opening music and waves crashing into the rocks, specifics didn’t last. Dark Shadows was one of the earliest fan-congregating shows. Before Comic-Con, there were Dark Shadows conferences. Kids eagerly bought all things Barnabas related.

I was about seven when the show hit its zenith. I do remember watching it, and the wonderful, creepy feeling it gave me. As a child I couldn’t have named any of the actors. A lot was happening in my life at the time. My mother was divorcing my alcoholic father. My grandmother, who lived with us, lay bed-ridden and dying in what had been our dining room. We lived in a run-down old apartment with very little money. Heavy stuff for a kid. And television also offered funny shows in the evening. And Saturday morning cartoons (which included, yes, Scooby-Doo). I’ve always been amazed at just how much stuff there is in the world and I yearn to understand it deeply. It was probably pretty much fore-ordained that I would try to be a professor.

Reading the Almanac not only reinforced how influential the series was, it also made me aware of just how complicated producing a television show is. Many, many people are involved, specialists in artistic and technical fields. Most of them make modest livings with, if they’re lucky, mentions in the credits. The stars we know. I think, for me, Barnabas Collins was a father stand-in. What I noticed, even as a child, was that he was sad. A certain type of person is drawn to sad individuals. I always want to cheer them up because I know how it feels. This is the part of me that wanted to be a minister. I tried that a number of times but it never worked out either. Reading an almanac like this isn’t really a deep intellectual exercise, but it is a learning experience. And one of the things we might learn about is ourselves, whether a true fanatic or not.