While at Mystic Seaport yesterday epiphanies of America’s religious life lined up to be encountered. The museum owns the Charles W. Morgan, the last surviving American whaler from the nineteenth century. The connection between whaling and religion is, as I’ve posted about before, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. Whaling was a barbaric, inhumane business – particularly for the whale – but it had all the justification that BP or Exxon still utilize in the destruction of our oceans: the product is in demand and pockets are very nicely lined indeed. Moby Dick is, however, the story of an inaccessible, at times angry god, who leads to death as easily as enlightenment. The Morgan is dry-docked undergoing extensive restoration, yet is still open to the public. Stooped over in the blubber room, imagining the horrors of the place, Melville was my only comfort that something akin to nobility might have come from whaling.

The Seaport also offers an exhibition called “Voyages” – a look at the way the sea has played and continues to play a role in the life of an America that most people associate with a large swath of dry land. The first display tells the story of a family of Cuban immigrants rescued from a tiny fishing boat while trying to get to the United States. A nearby display features Neustra Senora de la Caridad del Cobre. This mythological character is a goddess emerging from the conflation of the Virgin Mary and the African goddess (through the mediation of Santeria) Oshun. The story of the Cuban family associates the origin of this goddess’s concern with seafarers through the chance find of a statue of the Virgin floating at sea near Cuba in 1606. Our Lady of Charity, the Catholic version, is the patron saint of Cuba, and the syncretism of these goddesses has led to a new mythological character on view in Mystic.

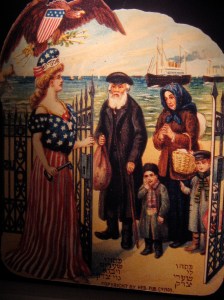

Further along in the same building, in the story of immigration, is the painting shown below. A Jewish family is shown disembarking before a Lady Liberty with “America” written on her crown in Hebrew. The inscription on the sand asks whether the new world has room for the righteous. It is a poignant reminder that acceptance in the United States religious world is often a difficult one. Even today non-Christian religions are viewed with suspicion by many in America. The sea has brought us all together, however, since historically immigration has meant crossing the great waters somehow. One of the gifts of the sea that we are still struggling to grasp is what it means truly to offer freedom of religion to those from far distant outlooks in a world that daily requires less of the gods.