I can never keep track of the vernal equinox. Actually, I have the same problem with the autumnal equinox and both solstices. I think it’s because when I was growing up I thought they always came on the 21st of the month. That’s a nice, regular interval. Our months, however, are not natural. Were they to follow the moon (whence we get the word “month”) they would be about February length. The moon’s phases, however, do not keep to human time. In actuality, a month is approximately 29.53 days. Various emperors throughout history added days to their months, making our jumble of 365.25 days a mix of mostly 31-day periods, with some being 30, and February alone holding out at 28. Or 29, depending. All of which is to say, I didn’t realize spring was here until the day was mostly over. Here in the northeast it was snowing, and the celestial dome was occluded. That was a shame since it was also the day of a solar eclipse. I consoled myself by realizing that even if it had been sunny I was in the wrong location to see the eclipse, so I wasn’t missing much.

So spring subtly appeared this year. Not only was the day an eclipse day, for some, it was also a “supermoon” day. That is to say, the moon was at its closest point to earth at the time, making the eclipse a truly spectacular one, if you could see it. All of these astronomical machinations on the event that sets the date for Easter has developed a new kind of mythology. According to The Guardian, some minority of clergy have seen this event as initiating the apocalypse. Of course, eclipses are by their nature local events. The vernal equinox occurs every year, and the first Sunday following the first full moon of the equinox will be Easter. We get a supermoon (or perigee-syzygy of the Earth-Moon-Sun system) about every 14 months, so this is hardly rare. But then, the moon has always been the locus of mythology.

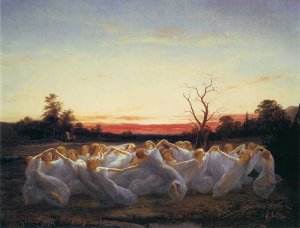

Ancient peoples knew the phases of the moon intimately. As the main source of non-artificial light at night, it was a boon to those without electricity, or even gaslight. Without physics to provide a mechanism, stories developed to explain the ever-changing status of our nearest neighbor. Some of those tales took on religious elements, and many religious calendars remain lunar. The vernal equinox, however, is a solar event. From now on the days will get longer until the summer solstice, a day of celebration and mourning, as we move back into the days of declining light. Each of these celestial events comes with its own religious freight, and it seems, dissenting clergy notwithstanding, that so it shall carry on for many moons to come.