Nancy Gibbs’ essay “Creation Myths” appears in this week’s Time. Leaping off from Craig Venter’s “creation of life” in the laboratory, Gibbs asks who the final arbiter might be in this world we’re creating in our own image. The more I ponder the question, the more I realize that no person really decides how far we will go and the implications will only grow more and more unanswerable. We all attempt to construct the world according to our idea of how it should look; it is not a question of if we create the world in our image as much as it is whose image will prevail. As I noted in a recent post, no one person has all the answers. What each of us does impacts all the others just as a wave influences everyone in the sea. We fear science taking the prerogative of creating life because we are fully capable of imagining where it might go, but we just don’t know.

As an individual who has often been on the receiving end of other people’s visions of how this or that institution or company should look, it is my humble assessment that we have already lost control. We never really had control in the first place. At the end of the day, who will really be able to prevent another Gulf oil spill from occurring? Make what laws we will, other creators will find ways around them. And as in Gibbs’ article, the rest of us will simply have to react. No one is really in control.

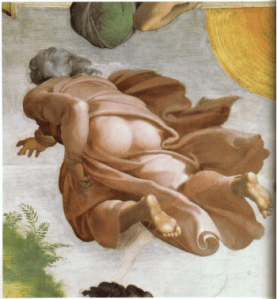

Perhaps this is the real reason that religion is so appealing. It is terribly, terribly convenient to have an omnipotent divine entity on whose anthropomorphic shoulders we might cast our worries and burdens. Whether we believe in predestination or not, it is comforting to suppose that when it is all over God will somehow sponge up all that oil (preferably squeezing that sponge back out into BP’s great, sturdy tankards of crude), or stop that evil clone we’ve engineered, or stomp out that hyper-aggressive virus we’ve unleashed. We may make laws against creating life or human clones in the laboratory, but it will happen nevertheless. Gibbs wonders if scientists are about to cross some moral Rubicon. My answer is simple: we crossed that Rubicon long before the river itself flowed, when we first put our webbed feet out onto dry ground and began our still uncertain journey to the future.