It takes one to know one—or so they used to say. My current preoccupation has me learning about the Romantics. This isn’t the same as “romance,” although both words derive from the Old French for “verse narrative.” Novel, in German, is Roman. In any case, Sir Walter Scott cordially embraced Washington Irving when the latter arrived unannounced at Abbotsford. Reading the account in Irving’s own words, it sounds like a bromance, and some modern interpreters—inclined as they are to look for genital contact—have suggested Irving, a lifelong bachelor, might’ve been a homosexual. Although there’s nothing wrong with that, I do wonder if it misunderstands the language of the Romantics. To borrow a sentence from Andrew Burstein (more to come anon): “This had to do with intimacy, not sex as we understand it.”

I recently gave a talk about Herman Melville’s spiritual orientation. I mentioned his close friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne. During the discussion period the question of whether they might’ve been lovers was raised. I’d read this before. I don’t know what went on in Melville’s bedroom—it’s none of my business—but I think the Romantics were all about intimacy. We’re now familiar with the genre of bromance. Guys, usually two, pairing off for pursuits of significance to both of them. Or two women. I think of all the great same-sex pairings throughout literary history and wonder where we’d be without them. Since our culture has long demonized sex, our mind is constantly creeping between the sheets. Who touched whom? Where and when? Isn’t intimacy enough any more? Where’s the Romance? I’m no prude, but I wonder if we misread sex and the Romantics.

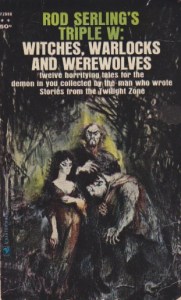

The Romantic Movement produced the culture I taught myself living in a run-down house with no spending money. I borrowed recordings—actual records—of Beethoven symphonies from the library that I had to listen to with headphones because nobody else wanted to hear that kind of thing. I read Poe. I read about Poe. Gothic, a subset of Romanticism, became my muse. I had no intimate friends with which to share this. Not until seminary—that place where such unusual, unspoken things occur. Of course I was in Boston, the most Romantic of American cities with New Bedford to the south and Salem to the north. To the east the boundless ocean. We still read the Romantics. We still read about them. I can’t help but think we might misunderstand them. Yes, Irving and Scott were together “from morning to night,” but thinking back to my own Romantic ideals as a teenager, I suspect they just talked. Intimately.