After writing a post on Natib Qadish, a modern revival of Canaanite religion in the United States, I received some comments from Lilinah of Qadash Kinahnu, another modern Canaanite religion revival. These movements are a fascinating development in an overly technological era — both movements have online resources that include serious scholarly treatment of ancient religions of the Levant. Both appear to be sincere attempts to get in touch with what modern religions seem to have lost. Both have heard the call of Balu.

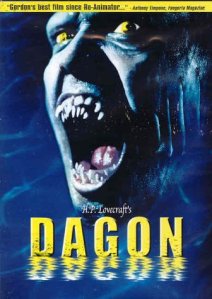

In a society where universities seldom offer programs to study the Ancient Near East, people are starved to know about it. I realize that the field of study will never bring in the money that the sciences or finance do, but obviously there is something deeply satisfying about it. And students are hungry for it. Not only appreciated by those who start revivals of ancient religions, many of those who read more recent popular treatments are intrigued. Neil Gaiman’s American Gods was a New York Times bestseller. Although much belatedly, H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos has become a paradigm for many undergraduates I’ve met. I was reminded of this as I watched Stuart Gordon’s 2001 movie entitled Dagon. A relentlessly tense and macabre film, the Lovecraftian base assures a constant draw for those who hear the call of the ancient deities.

In a society where universities seldom offer programs to study the Ancient Near East, people are starved to know about it. I realize that the field of study will never bring in the money that the sciences or finance do, but obviously there is something deeply satisfying about it. And students are hungry for it. Not only appreciated by those who start revivals of ancient religions, many of those who read more recent popular treatments are intrigued. Neil Gaiman’s American Gods was a New York Times bestseller. Although much belatedly, H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos has become a paradigm for many undergraduates I’ve met. I was reminded of this as I watched Stuart Gordon’s 2001 movie entitled Dagon. A relentlessly tense and macabre film, the Lovecraftian base assures a constant draw for those who hear the call of the ancient deities.

We love technology. I’m posting this entry on an internet where ideas are simply electrons forced into recognizable patterns. We can’t imagine what life was like before being able to communicate with people just about anywhere in the world instantaneously, and where we can live our entire lives without ever actually touching physical money. Over all the noise of technological progress, however, can be heard the distinct call of Balu — a call to a simpler era, pre-Christian, pre-Judaism, pre-Iron Age. It was an era when human destiny fell into the hands of ancient gods.