Biblical literalists make strong claims for selectively obeying the Bible. It isn’t so hard to do in the short term, as numerous books on people “living biblically” have shown. You can get by for a year without trimming your beard or going out on a Saturday. You can even survive without eating pigs. Still, the moral codes that political literalists cite tend to have their own empowerment in mind: prevent women, gays, or those of other races from getting ahead. Stone adulterers and sassy kids. The Bible will set us straight! The finer points of the law, however, have likely never been observed. Even biblical scholars will confess that Leviticus can be a tough go. It sometimes helps to make diagrams as you read along to try to follow the intricate rules. Still, since Leviticus is the only place to find anti-homosexual rhetoric in the Hebrew Bible, we’d better go on reading it, right? It is worth it to feel better about ourselves. Superiority rules!

I was thinking about Leviticus 25 recently, the chapter about the sabbaths of the land. The concept may have sound environmental principles encoded in it: after working the land for six years, you leave it fallow on the seventh and live off of what you’ve stored up during the presumably bumper-crop years. The same principle lies behind rotating crops—the land needs a rest. There’s no evidence, however, that this was ever really put into practice. It is notoriously difficult to feed everyone in a subsistence economy, and deliberately not growing food for a year will almost certainly lead to disaster. Read a little further though. Every fiftieth year, Leviticus 25 mandates, that which you have bought from your neighbor should be returned. “Ye shall not therefore oppress one another” is one of the more easily overlooked rules in the Good Book. Any land sold is only on loan for, at most, forty-nine years. I’m still waiting for the book entitled My Fifty Years of Living Biblically.

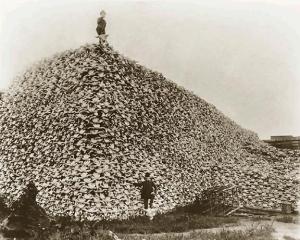

The biblical term for this collective lack of selfishness is called Jubilee Year. Ancient Israel was, at least on vellum, an egalitarian society. Each person had promised land allotted to them. Economic hardship (such as sending a child to college) might necessitate selling all you have. Fear not—hopefully before you die—what you sold will be retuned to you and the system will even itself out again. It is a profoundly beautiful idea. It has, of course, never been taken seriously. So as we see the literalists massing as candidates begin gearing up for another cycle of elections, I think it is only fair to ask to see their mortgage papers. A visit to the county records bureau might be in order. I think maybe somebody has been holding out on land I’m biblically owed in upstate New York. Just don’t tell any Native Americans about this, for it seems maybe they have the most of all to benefit from taking the Bible literally.