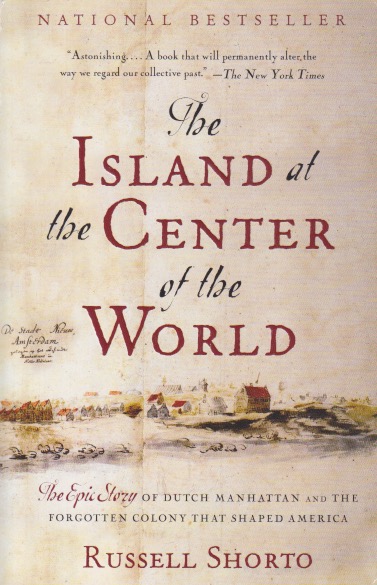

Serendipity may have been over-used in the eighties, but the idea of finding something by chance that turns out to be really good is real enough. My wife found The Island at the Center of the World, by Russell Shorto, by chance. You see, used bookstores are places of serendipity. This one happened to be in Trumansburg, New York. Subtitled The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America, this is the story of an early European incursion into North America. These days it’s difficult to feel good about any of that, but overlooking the misery we’ve caused for a moment, the early Dutch settlement was, comparatively, not as detrimental to the American Indians as later colonies were. The Dutch were mainly interested in trading, and unlike the Puritans who settled to the north, they were tolerant of difference, even religious difference.

Shorto chronicles how the settlement of Manhattan from the beginning was one of diverse peoples having to get along and accept one another. The Dutch, like the Puritans, had been infected by Calvinism, but they took a more practical view. People get along better if you don’t force them all to think the same way. The book suggests that this was impressed on New Amsterdam from the beginning, and it remained when it became New York. It’s a fascinating story partially because it begins the narrative before the point where we’re generally instructed in school. Europe was warring, at the time, of course. But it was a Dutch idea—that peace could be the default state, instead of war—that allowed for real civic progress. Those scrambling for empires, however, continued to squabble, even as they still do today.

There are plenty of unexpected insights from this book. The Dutch in many ways molded the die that would become European America. Having built a successful trading colony in Manhattan, they had to surrender it when the English, after the Cromwell debacle, decided to take it by force. The people of Manhattan did not want to fight a clearly superior army and lose all that they’d gained by their tolerant way of life. And so New Amsterdam became New York. The story is filled with colorful characters and incidents that, if you’re like me, you’ve never heard of. I’m not one of those people who has to read everything published on New York City. Working there for many years was sufficient for me. But still, this is one of those books that I’m glad my wife serendipitously found while looking for nothing in particular in a used bookstore.