One figure among the standard repertoire of Halloween characters has never appeared on my list of favorite monsters. I suppose it may be because as a child I fervently believed there was a devil that he never made my A-list. Satan was real, according to my church, in some almost biological, corporeal form. Even as a youngster I knew vampires, werewolves, Frankenstein’s monster, and the rest, really didn’t exist (even after I hid under my covers all night once, after putting my head down on a bat that had flown into my bedroom). The devil was, however, biblical. And I never felt tempted to dress up with red horns and pointy tail, carrying a plastic pitchfork. Halloween was always among my favorite holidays, but it was for pretend monsters and ghosts (which might perhaps be real, but which were not diabolical, according to my childhood economy of the spiritual world). The consequences of devil imitation seemed eternal, and even today, in the rational light of the twenty-first century, I can still be given pause even though I know the concept is a Zoroastrian one that morphed into early Christianity’s need for a kind of anti-Christ.

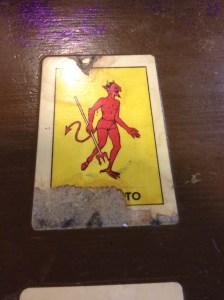

There are many who still believe in a real devil. Some branches of Christianity (and Islam) teach that a literal devil lurks about in our world. In western culture he is a figure instantly recognizable, although there are differences of opinion in his anti-iconography. Last weekend I visited a fine little restaurant in a New Jersey town that has a reputation for being haunted (the town, not the restaurant). It was a seat-yourself day and the table my wife and I ended up selecting had shellacked cards on top as part of the decoration. There in front of me was the devil. I pondered this. The cards, all captioned in Spanish, had mundane subjects: an umbrella, a musician, plants, a spider (okay, so that last one’s a little scary too), but only one supernatural figure. Perhaps the entire deck, had I seen it, might have had more. No doubt, for a world that postulates a good God, a devil covers, well, a host of evils.

The word “devil” is somewhat loosely applied these days. New Jersey has its own cryptid called the Jersey Devil, which has led to iconic names for sports teams and perhaps a public official or two. But even in the aftermath of 9/11 there were those who seriously postulated seeing the face of the devil in the tumbling debris of the twin towers. For a character of the religious imagination, the devil has managed to impress deeply on the human psyche. I know in my rational mind that I should simply dismiss all of this and get on with the business of enjoying the monsters that will show up at my door later this week. Nevertheless, when the waiter comes out with our food, I look down at the table and decide to pass on the hot sauce for today, just in case.