By my best reckoning, Thanksgiving has not yet taken place this year. Since Halloween, such as it was, is now over, we must still be in November. As I was exiting my office building last Wednesday, I noticed that the holiday tree was already going up in the lobby. A few blocks away and I heard the first Salvation Army bells of the season and shouts of holiday cheer. The great tree in Rockefeller Center was being erected. (I picture burly guys with a super-sized tree stand swearing in the cold air—”Left, nudge it to the left!”) Maybe it’s just a storm-weary city glad to be rid of Sandy, but it does seem to be a bit early to me. Holidays, in any modern sense of the word are about opening wallets and injecting cash into the system. The very corpuscles of capitalism. I enjoy holiday cheer as much as the next guy or gal, but I don’t mind waiting for it to arrive. Antici-

Holiday seasons are as old as holy days themselves. In our work-obsessed culture, however, convincing bosses of the regenerative utility of granting more than a single day off at a time is an uphill battle. Productivity is what we’re all about. And so we lengthen our public show of holidays instead. Thanksgiving’s not much of a banker except for grocers, and although turkeys may make great primary school decorations, they don’t really match the productivity and professionalism that corporate offices like to promote. The December holidays, however, give us Black Friday. Listening to the news over the last few days, it is clear that many people are biding their time, already ready to get those distant family members out the door, and let’s get those bargains! pation.

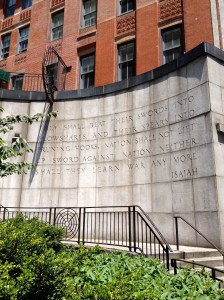

Holidays reflect what we hold sacred. I’m not one of those purists grinches who see gift-giving as some inherent evil—in fact, giving things away is one of the under-utilized tenets of most major religions—but I do wonder how much of it is an appeal to the ego. I feel good when I make someone else happy. Yet at some level, I’ve indebted them to me. I’ve made a business deal. The holy days have been infected with capitalism. Warm memories of not having to go to school for nearly two whole weeks, being with my family—the place I was unquestioningly accepted—and getting presents as well? What could be more sacred than that? But I’m getting ahead of myself. It is still mid-November. After all, Black Friday (and what’s that day before that called?) hasn’t even started yet.