Among the most respected of intellectual endeavors is political science. Analysts who read and reason beyond national borders, finding implications in countries many of us have never heard of, they can be an intimidating lot. Experts in economy and psychology, they tell us what the big picture looks like—why we do what we do. And almost universally they disdain religion. We’re talking politics here, why don’t you go sit at the kid’s table? Religion is the stuff and nonsense of make-believe. What politics is about is who has the biggest bombs and bank accounts. Those who impact the world in real ways. And yet.

I would never claim to be up-to-date on current events. I don’t have time to read newspapers and if my friends didn’t send me pertinent articles now and again I might still believe that social justice is more important than the color of an anonymous dress. When no less than an authority than the New York Times speaks, however, I do have to pause a minute or two to consider the implications. Frank Bruni has recently been writing on the Opinion Pages about those ultimate strange bedfellows, religion and politics. I may have got the order wrong, but that’s for political scientists to determine.

Many people don’t consider that religion can be, in some respects, scientifically analyzed. As a deeply divided nation, one factor that even political scientists should note is that yes, religion does count. No matter how naively conceived, people vote with their faith behind that polling curtain. The Republican Party realized this in the 1980s. If you take just one or two religious issues and make them the platform on which you stand, you can garner a disproportionate amount of the conservative evangelical vote. A new study from the Public Religion Research Institute, according to Bruni, demonstrates just how disproportionate the outcome can be. Surveys may not be precise, but less than 20 percent of Americans are white evangelical Protestants. Yet their issues are the ones that make or break elections.

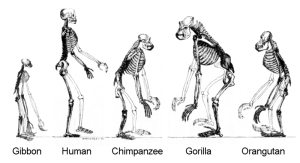

Life has a way of making one cynical. I grew up a white evangelical Protestant. Although my viewpoint has evolved with my education, I can’t shake two of those qualifiers even if I want to. I read political scientists dismissing religion as a bogus topic, mere twaddle to fill the daub of inert minds walled in by primitive thinking. And I read the occasional news story that demonstrates that the facts don’t fit the premise. Do we need to understand religion? Absolutely not, I’m told. But in the end, even the analysts of the political beast will have to realize that tails wag dogs just as surely as raising hackles will make any mammal appear larger than it really is.