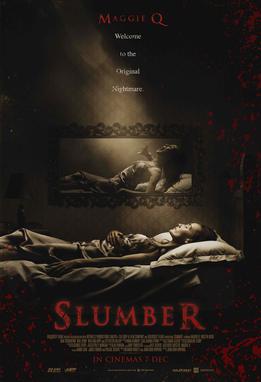

Sleep is pleasant but it’s such a vulnerable time. Something deep in our animal DNA tells us to find a sheltered place to do it. That vulnerability is compounded by demons. So claims Slumber. While not the most original story, it’s pretty effective for a while, but then holes begin to appear in the plot and you find it difficult not to keep asking why the problems weren’t addressed. Let’s take a step back. Doctor Alice Arnolds lost her younger brother to a demon when they were children. This demon, called Mare, causes, well, nightmares. These nightmares lead to sleepwalking and ultimately death. As a doctor specializing in sleep disorders, Arnolds helps others scientifically. She’s come to believe that her brother’s death was because of natural causes—the supernatural doesn’t exist.

Okay, so sleepwalking is creepy, and the idea isn’t a bad hook. Then Arnolds meets a family of four, all of whom sleepwalk with nightmares. The demon’s target here is their young son, who reminds Arnolds of her lost brother. At the sleep clinic the monitors show something odd, but circumstantial evidence points to the father as the guilty party. But here’s where the big hole appears. Once Arnolds becomes convinced something supernatural is happening, she decides to handle it herself, at the family’s home. Even when it’s clear they’re out of their league, nobody calls the police or even an ambulance, let alone a priest. Instead they rely on a janitor’s father whom they’ve just met. They try to keep the boy awake until they’re endangering his life, then they fight the demon in their dreams. There is a kind of twist ending, and the production values are good.

The demon, which Arnolds researches on Wikipedia, is a notsnitsa. Why this Slavic demon targeted both her brother and the family under distress isn’t explored. The connection is made with “the night hag”—a folkloric demon that attacks in your sleep and is generally explained as sleep paralysis. This is not a possessing demon. In the film it’s said to be parasitic, and the sleeping victim acts out what the demon tells it to do. The lack of any religious tension hurts this movie. As does that lingering question—why not call in some kind of expert? Either sacred or secular will do! I won’t ruin the ending of the movie, but I’ll warn those tempted to watch to come armed with a great deal of suspension of disbelief. You’re gonna need it.