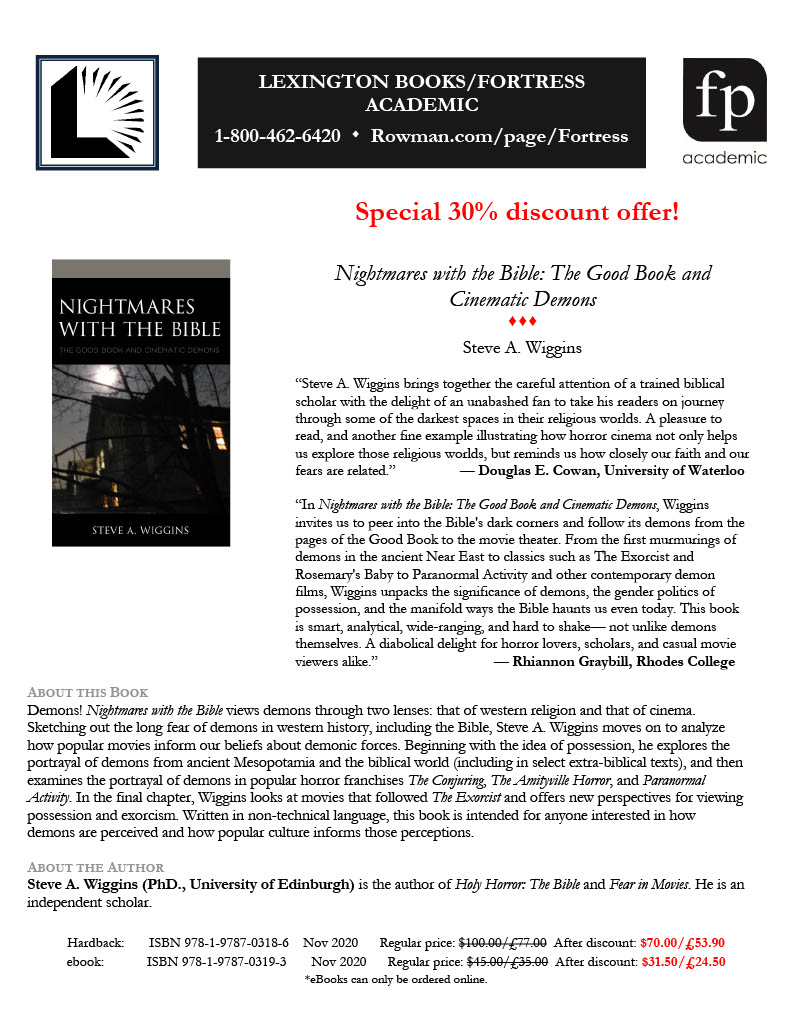

While recently in touch with a colleague I’ve never met, I agreed to send along a filmography of my two horror movie books, Holy Horror and Nightmares with the Bible. I tend not to read my own books after sending them to the printer. Defensively it might be that I can say, “I know what I wrote,” but in reality it’s probably more a lack of self-assurance. Writers often experience self-doubt and although you’ve convinced an editor and an editorial board you may still have your harshest critic to please. Even though you’ve read the book many times through—at least fifteen each for these two books—you fear you might’ve overlooked something. So it was strange trying to recall which films I’d actually discussed. Or how many.

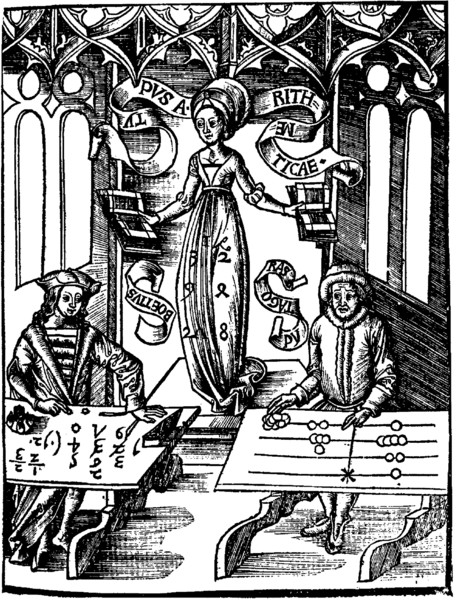

The latter point became clear in a recent review on Reading Religion. Knowing how I went about piecing together Holy Horror, I’d forgotten just how many movies I watched and rewatched for it. While it was never intended to be a comprehensive treatment of the Bible in horror (I haven’t seen all horror films), it nevertheless ranges widely. After having submitted it I continued to watch horror and I continue to find various Bibles in it. The amazing thing is just how truly widespread the Good Book is as an iconic symbol. Indeed, I’d been reading about the Bible as an iconic book and that idea took hold in the early days of putting words down for the book. As an editor I help authors figure out these kinds of issues all the time. Physician heal thyself.

Even though Nightmares with the Bible just came out over a year ago I couldn’t list all the films off the top of my head. Sometimes you need reminders. My books are never discussed at work. The people I interact with on a daily basis have no interest in them. In other words, unless I’m having an interview or reading a review, I don’t have much opportunity to think about them. I’ve moved on to my next projects. The draft of The Wicker Man has been submitted and I have three promised articles to work on. Still, I’m trying to settle on the next book. I seem to have found some acceptance among the horror crowd. Biblical meteorologists and researchers on Ugaritic goddesses are much less seldom in touch. Monsters are often mixed forms. I should know that after watching all these movies.