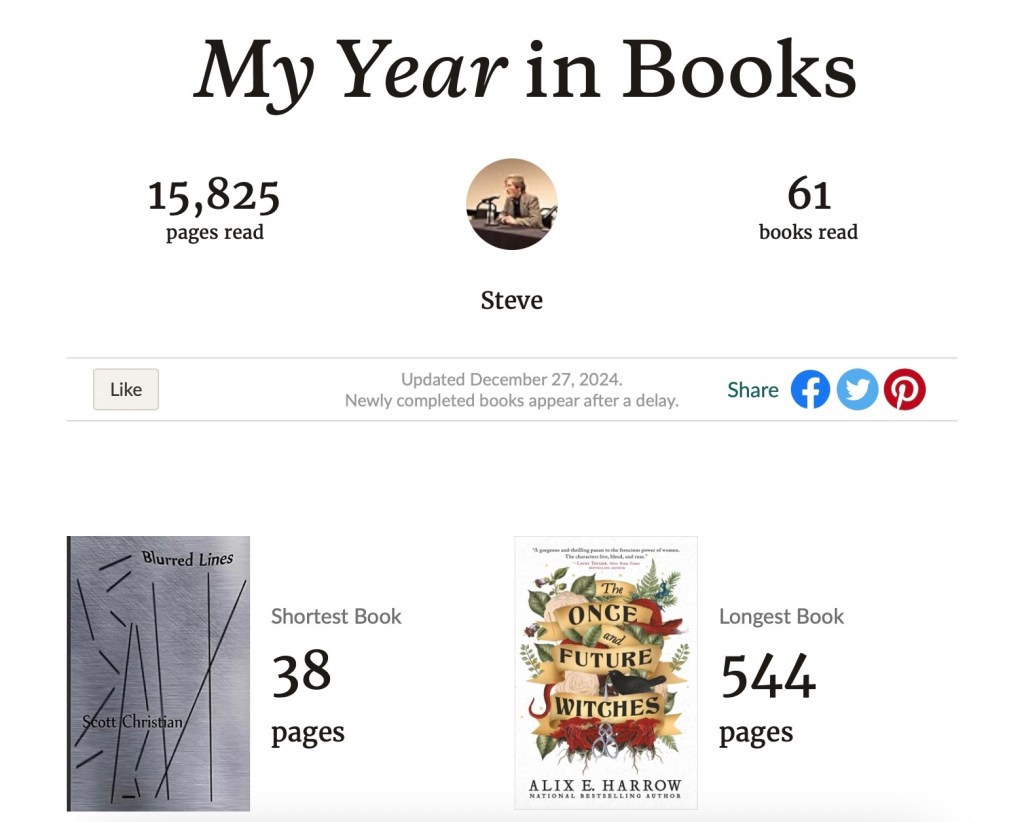

So, my first royalty statement for Sleepy Hollow as American Myth arrived. It is my poorest selling book ever, not even notching up to Nightmares with the Bible, and that one was twice as expensive. A couple things: I know that nonfiction books had a hard year last year. Also, “academic” books tend to do better in the subsequent years after their initial release, for those of us with no name recognition. In any case I’ve decided to try focusing on fiction. The compulsion to write is deep-seated in me. My nonfiction books are creative explorations of ideas neglected or never before brought together. They’re also priced too high for the trade market. I was pleased to see, recently, that The Wicker Man is now in over 400 libraries, according to WorldCat. That makes it my second best-selling book, after Weathering the Psalms. A Reassessment of Asherah has been viewed over 9000 times on Academia.edu.

So, fiction. I write my fiction under a pseudonym. I currently have one novel out for consideration and another very close to being ready. I have several in the wings. What strikes me as crazy about all of this is that I’m told (as I have been since high school) that my writing is quite good. I’m not the one to assess this claim, since I’m far too close to it. It does make me wonder, however, what it takes to earn a little cash at it. My last royalty check for a new book was half of what they usually are. Good thing inflation is under control and the economy booming. So I hear. I do believe that the most impactful books tend to be fiction. People like a good story. And they can last for many decades. The nonfiction that stands the test of time is a very narrow shelf indeed. At least compared to our fictional siblings.

For fiction you need to keep at it to improve. I think of all the years I’ve poured into my last four nonfiction books. The only real critique I’ve seen of Holy Horror was that it was “too well written.” When’s the last time someone said such things about fiction? Oh, I’ve got three nonfiction books underway as well. One of them I’m quite excited about. But then I take a look at this royalty slip sitting in front of me and wonder if I’ll ever learn. I have to write. I’ve done that since fifth grade as a means of coping. Here I am at over half a century at it. There’s no danger of giving it up now. But the form it may take, well, that’s up for grabs.