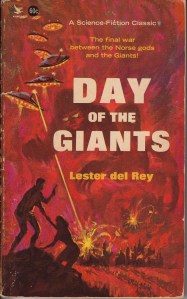

Coming back to a book you first read as a tween, in the days before tweens even existed, can be a revelation. Lester del Rey’s Day of the Giants introduced me to Norse mythology as a kid, and, along with Thor comic books, was my Nordic Bible. The last time I read it was probably in the Ford administration. As part of a reading challenge I’m undertaking this year, I had to select a book I’d read before and, amazingly enough, I still had my copy. Reading the book as an adult, however, proved a very different experience from reading it as a child. For one thing, I noticed quite a bit more of the implicit theology of the story. Del Rey was no theologian, of course. This little book, however, makes a statement that is difficult to miss regarding the gods: they are victims of tradition.

Coming back to a book you first read as a tween, in the days before tweens even existed, can be a revelation. Lester del Rey’s Day of the Giants introduced me to Norse mythology as a kid, and, along with Thor comic books, was my Nordic Bible. The last time I read it was probably in the Ford administration. As part of a reading challenge I’m undertaking this year, I had to select a book I’d read before and, amazingly enough, I still had my copy. Reading the book as an adult, however, proved a very different experience from reading it as a child. For one thing, I noticed quite a bit more of the implicit theology of the story. Del Rey was no theologian, of course. This little book, however, makes a statement that is difficult to miss regarding the gods: they are victims of tradition.

It is probably not worth worrying about spoilers over half a century after a book was published, but I’ll try to be sensitive nevertheless. Leif Svensen, our protagonist, finds himself in Asgard on the eve of Ragnarok. All the familiar Norse gods are there: Thor, Loki, Odin, and kith and kin. As they prepare for the battle with the frost giants, who, in the mythology win the contest, the deities are decidedly subdued. They believe their fate is sealed by a prophecy of defeat. Leif, being a true American, gives them a rousing speech about overcoming the old ways. Gods, by nature, are conservative. They don’t have to bow to tradition—they are gods, after all. The deities are not swayed by the logic of a mere mortal, even after his apotheosis. Fate, it seems, trumps even gods.

I’m pretty sure that Lester del Rey wasn’t attempting to make any profound theological observation here. One can be an accidental theologian. Ideas of gods and what they must do can be a detriment to their own future. Even with the evidence of the failure of their own prophecy, the gods can see no way forward other than that they’ve recognized as fate. They are, without saying too much, out-maneuvered by human resourcefulness. A man tames his god, and it can become a man’s best friend. I wasn’t expecting such theological insight from a sci-fi book from my youth. Then again, you never know what may happen when you come back to a book after leaving it on the shelf for four decades.