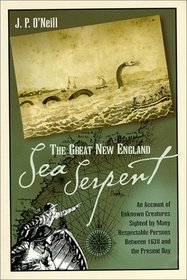

Seeing, it is said, is believing. I have a feeling that this truism may have become effaced somewhat in this age of deft photo manipulation and apps that are marketed to insert ghosts and UFOs into any picture. Nevertheless, anyone who has seen anything genuinely puzzling knows that it creates a lasting impression. A world without mystery, although a capitalist’s dream, is a nightmare for everyone else. So it was, now that October is here, I settled down with J. P. O’Neill’s The Great New England Sea Serpent. I found O’Neill’s book in a used bookstore a few weekends ago (appropriately water-damaged), and since I have a fascination with the ocean and monsters, this seemed like it would appeal to both of my avocations. It did indeed. O’Neill isn’t a sensationalist writer, but rather she is a normal person with normal jobs who has an interest in strange animals. Beginning in 1751 and up to three-quarters through the twentieth century, people had been spotting a classical sea serpent along the New England coast, and occasionally on ocean voyages across the Atlantic. Of course, we’re told, sea serpents don’t exist.

Seeing, it is said, is believing. I have a feeling that this truism may have become effaced somewhat in this age of deft photo manipulation and apps that are marketed to insert ghosts and UFOs into any picture. Nevertheless, anyone who has seen anything genuinely puzzling knows that it creates a lasting impression. A world without mystery, although a capitalist’s dream, is a nightmare for everyone else. So it was, now that October is here, I settled down with J. P. O’Neill’s The Great New England Sea Serpent. I found O’Neill’s book in a used bookstore a few weekends ago (appropriately water-damaged), and since I have a fascination with the ocean and monsters, this seemed like it would appeal to both of my avocations. It did indeed. O’Neill isn’t a sensationalist writer, but rather she is a normal person with normal jobs who has an interest in strange animals. Beginning in 1751 and up to three-quarters through the twentieth century, people had been spotting a classical sea serpent along the New England coast, and occasionally on ocean voyages across the Atlantic. Of course, we’re told, sea serpents don’t exist.

The Great New England Sea Serpent is a compendium of sightings from many reliable witnesses over the centuries. Of course, to many it is impossible. To me this appears to be the same kind of arrogance we apply to the universe—if we haven’t catalogued it by now, it doesn’t exist—to suggest there are no monsters of the deep. As any oceanographer will tell you, we know more about the surface of the moon than we do about our own oceans. If you turn your globe (or app) just right, there are views of our planet where virtually no land is visible. We are a watery planet. Even with current technology, the deep ocean is difficult, and very expensive, to explore. Who knows what might be lurking there right off the bow? O’Neill’s account is full of old salts and snarky journalists, but at the core of it all is a humility in the face of the largeness of the sea. What do we really know?

Of course, there is a fear of literalism. The Bible (and other ancient texts) take sea monsters for granted. Leviathan is a dangerous beast and, no matter what the pundits say, is no crocodile. And yet, for the past several decades the reports of the New England beast have dried up. Where has our beloved sea serpent gone? I have to wonder with both our polluting our oceans and our increasingly efficient (and massive) ships, if we haven’t simply forgotten that ancient maps used to leave space for dragons. Our great ships, guided by GPS, and our oceans running a temperature, are sure signs that greed has surpassed wonder. Have we, in our self-centeredness, slain the last of our dragons? O’Neill, please understand, does not call them dragons. Hers is a sober and straightforward account. But when October comes I just can’t help but hope there are still some monsters out there, deep under the waves.