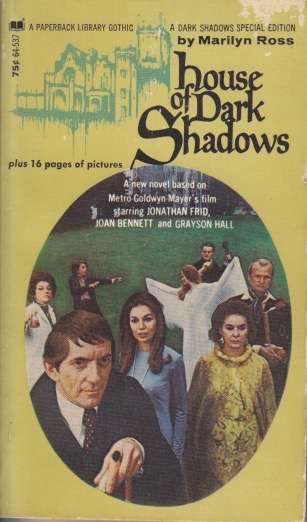

Last year I completed an odyssey that began over a decade and a half ago. I finished reading the Dark Shadows serial novels by Marilyn Ross. Not because they were great literature, but because they were an important part of my childhood. Slowly, over the years, I regathered the books and read them until the whole series was done. One of the used book sellers was offering a collection of the books, and although the collection had some duplicates of what I’d already found, it contained some of the more difficult to locate titles. When it arrived, I found it also included House of Dark Shadows. This novelization wasn’t part of the series, and like most things in my life, I can’t claim to know everything about Dark Shadows. As a child I didn’t know there had been a movie, let alone a novelization. (I bought the books as I happened to find them, at Goodwill and watched the TV show.)

In the present, I’d just finished Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Talents and felt that I needed something lighter for my next fictional project. House of Dark Shadows proved a better read than most of the series books, perhaps because it was based on a movie script written by the screenwriters. Marilyn Ross was actually William Edward Daniel (W. E. D.) Ross, and he wrote more than 300 novels. His Dark Shadows oeuvre became repetitious in its dialogue, across the series. His characters always seem to say “at once” instead of “immediately” or “right now.” I’m pretty sure the word “mocking” appears in each of them—certainly the latter ones—multiple times. Having the script must’ve really helped keep those trademarks to a minimum.

Of course, now that I’ve read the novelization I need to go back and watch the movie again. It’s been almost two years and some of the details escape me. It’s largely because the movie goes “off script” from the long-running daily show (and the other novels). I also realized that Tim Burton’s Dark Shadows movie was really a kind of reboot of House of Dark Shadows, unfortunately screen written by Seth Grahame-Smith as a comedy. I’m no expert on Dark Shadows, just a reasonably enthusiastic fan in search of a lost childhood. The movie makes the premise of the series untenable—both can’t exist in the same world, so it’s kind of a Dark Shadows multiverse, rather than a simple universe. And it’s very complex. I’d need to start again at childhood to become an expert in it, but at least now I’ve read all the books.