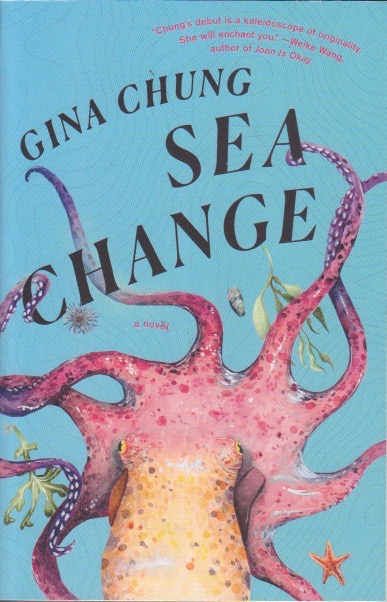

Sea Change is a probing story of learning to live with loss. Of learning how to say goodbye. I’m sure that I didn’t catch all that was being offered in this novel, but for those of us who did grow up without a father there’s a kind of therapy here. I know that I eagerly awaited the end of work each day so that I could pick it up and read a bit more. Framed as the story of the only child of Korean immigrants, the novel features Aurora (Ro), a young woman who has had to find her way ever since her father has gone missing. And even before that, actually. Her father, as a marine biologist, had captured an octopus (Dolores) who now lives in the aquarium where he once worked. Ro, whose relationship with her mother is strained, takes a job in the aquarium after her father goes missing and befriends the remaining part of him—Dolores.

At the same time Ro’s boyfriend is accepted into a mission being launched to Mars. (This isn’t science fiction, just to say.) The loss is another deep cut to a woman who had to deal with the earlier significant loss of her father. I won’t say much more about the plot since I think you should read the book, but it is a thoughtful, and from my experience, realistic journey through the mental states of those who cope with abandonment issues early in life. Of course, I can’t speak to the experience of being a child of immigrants, but the novel shows we all deal with the same kinds of issues, no matter where we’re from. At least we do in modern civilization.

Sea Change made me ponder, however, whether children raised communally would feel the same kind of loss if a parent they didn’t know was theirs left. The mother-and-child bond is a deep one, so I guess it could be that fathers, after conception, would be expendable in such a situation. It’s difficult to project how such a society would work. The family unit is so deeply engrained into our experience that, unless a situation is truly dire, we know we can rely on our parents not to try to harm us, but rather to protect and love us. Those of us who grew up without fathers (I’m not sure if that’s the case with Gina Chung or not) deal with insecurity issues that never quite go away. This beautifully written novel was, for me, a healing kind of experience.