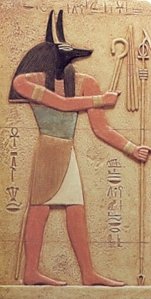

Although primarily known for his science fiction, Dan Simmons has also strayed down the dark path of horror fiction as well. During the depths of winter I found Simmons’s A Winter Haunting a moody and appropriate concomitant to the season. Not realizing that it was a sequel, when I saw his Night of Summer while at a Borders going out of business sale, I wondered if the same effect might work in warmer times. Both books rely on Egyptian funerary cult to move the story along, although in Night of Summer it is difficult to determine if the real menace is Osiris or the Judeo-Christian devil. Simmons has characters refer to Osiris as the power behind a haunted bell, but the climax of the story bears little resemblance to Egypt and quite a bit to standard monster flick tropes. “The master” of the reanimated dead is not explicitly identified. The use of Anubis in A Winter Haunting is quite effective, but the infernal characters were intermixed a little too much for my liking in Night of Summer. Better the devil that you know…

Perhaps it is simply that summer represents a time of relative ease and recovery from the frenetic pace of the remaining three quarters of the year. Although the heat and high humidity often make the season feel unbearable, the blush of abundance is all around. It is not easy to be afraid. When the air begins to chill and nature seems prepared to shut down production in the autumn, we naturally turn towards the desolate and constant struggle that will see us through the winter. Ancient people needed reassurance that warmth and relative ease would return. New Year’s rituals frequently marked autumn or spring, sometimes both. The death or life of the crops symbolized things to come.

Osiris, the god of the dead, also served as a god overseeing the renewal of crops for the ancient Egyptians. Death and life were knotted so tightly together that to unravel them was to fray the essence of the divine world itself. Among the cultures of the ancient world the Egyptians boasted the most developed concept of an afterlife. Even Paleolithic human burials contain grave-goods, demonstrating a belief in some kind of continuity beyond death. Simmons plays on that primal fear by resurrecting the dead in his novel. Beliefs about death and what might come thereafter have been one of the constant identifiers of religion from antiquity to the present. When evil pollutes the process the genre shifts to horror: witness the current fascination with vampires, zombies, and other undead entities. Religion and death are inextricably bound. Although Night of Summer may not live up to its sequel, the correlation between religion and fear meets the expectations of the genre, even during the long days of relative ease.