Out jogging last week, I was thinking about a harsh interview I once had. It was in Manhattan. The woman interviewing me made no attempt to hide her disdain. I’m not sure if it was for me personally or what I represent. She did not smile at all, not even for the usual niceties. She asked me whether I was better at speaking or writing. I said they were about equal. “No,” she briskly corrected. “Which is it, one or the other?” This came to me while jogging because I was reflecting that public speaking and writing are really the only two things I’m any good at, and I have worked on both for my entire life. These years later I still can’t say which is stronger. That was appreciated by my students and fellow scholars in my teaching career, if reviews are anything to go by. I like to communicate. (My wife might say too much so.)

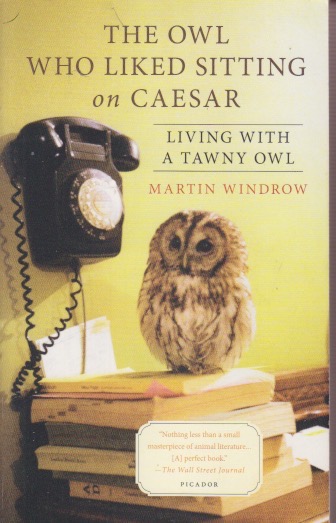

Owls are difficult to spot in the wild. Just last week I’d seen only my second in some sixty years. This was a screech owl. It’s not unusual to hear them when jogging at dawn. This time my right ear picked up on it more than my left as I jogged past a grove of trees. I looked but saw nothing. The trees were budding and some had small leaves already. I reckon I’ve seen my fair share of bald eagles. They’re large and they’re pretty obvious when they’re in the area. Owls are more secretive. Good at hiding. I reached the end of the path and turned around. As I reached the stand of trees, now on my left, it screeched again and I saw a blurred flapping of wings as it disappeared in flight. I couldn’t identify this owl in a line-up, but then again, that’s not something I’m good at. The voice is distinctive, however.

The person hiring is a bald eagle. Bold, aggressive, and sometimes literally bald. I’m more like that screech owl. Their public speaking is distinct and isn’t really a screech at all. I can’t speak for their writing ability. Life is our chance to come to know ourselves. We may think we have it figured out in our twenties, but each score of years makes you question past assumptions. Two things I always thought would be part of my career—public speaking and compelling writing—have both fallen by the wayside. At least professionally. What we say to others has an impact. Especially if we’re eagles. All things considered, however, I would rather be an owl.