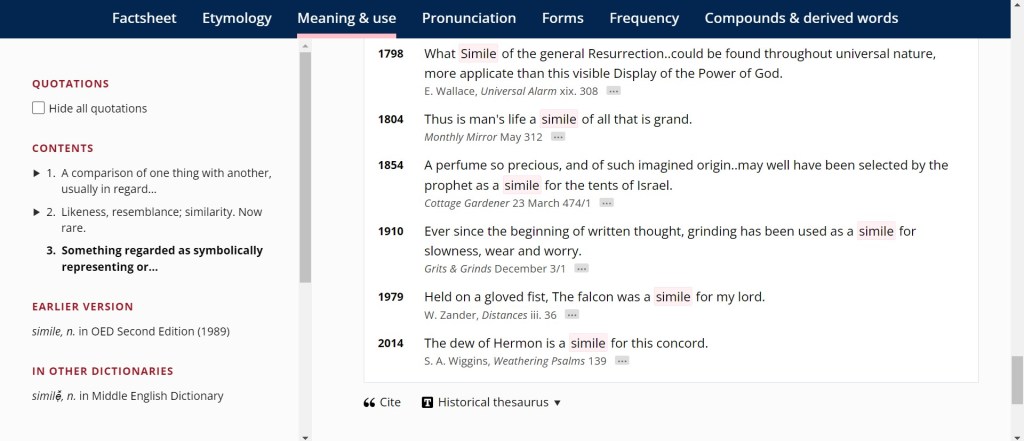

“Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace.” Thus begins the venerated Nunc dimittis, familiar from so many years of chanting evensong at Nashotah House. It comes to mind when I’ve reached a milestone I never dreamed of attaining. One that makes me feel as if I’ve accomplished my life’s work. Strangely, it didn’t occur when my name ended up in a study Bible’s front matter. But a friend recently sent me a note that immediately brought old Simeon’s words to mind. I have been cited in the Oxford English Dictionary. My book Weathering the Psalms is quoted (in the web version) under “simile.” I have no idea how examples are selected for the OED. It used to be scraps of paper sent in by astute readers, but I suspect things have changed. How my obscure book ended up there, I haven’t a clue.

There’s an irony here as well. Like most academics clueless about publication, I initially proposed Weathering the Psalms to Oxford University Press, assuming they published such things. It was turned down on the basis of a reviewer—one or two I know not—that I later met at a social function, where he was clearly embarrassed. I really just wonder how the OED found the book to cite in the first place. In terms of copies sold, it has been my most successful book, but that’s not saying much. As far as I can tell, it’s only sold less than 400 copies (the royalty statements don’t have the total and I haven’t received a check in years). I guess all things in the world are connected, whether we notice it or not.

Those who know me personally are aware that validation is a huge thing for me. I suspect that is true of most people who grew up in difficult circumstances and who managed—and this is never a certain thing—to pull themselves out. Having been fired from my long-term teaching post (where I was working on this book) only made me want to prove myself more, I guess. Insignificant things like getting a Choice review for one of my books (which continues to sell poorly) and having that behemoth of a dictionary notice that I used a fairly common word in a fairly common way do tend to release the endorphins. It’s like maybe someone noticed that I’ve passed this way. Maybe there was a reason for trying to capture the Wisconsin thunderstorms in a book about the Psalms. Maybe there’s a reason each working day there concluded with the Nunc dimittis.