While busy editing during the course of the day, I ran across this line in a Routledge book entitled What is Religion?: “We live in a pluralist, inter-racialist and multi-faith society and the need to understand one another is greater than ever before. Much misunderstanding arises from racialism and nationalism and could be avoided if people knew more about the beliefs and practices of one another.” Amen, Robert Crawford. I would, however, add a caveat to his statement: even more conflict could be avoided if people knew their own religions. I know many people, especially in the United States, who have no idea what their religion’s official teaching is. I know Presbyterians who have no concept of the official doctrines of this organization they’ve joined. Many Catholics, given the more corporate structure of that church, know the teachings but choose to ignore those that just don’t match the realities of life on earth. In such cases, the question of acceptance of religious teaching is a very relevant point. Can you get to heaven without crossing every “t” or, because it sounds more interesting, observing every jot and tittle? (By the way, “jot” is a stand-in for “yod,” the smallest Hebrew letter, “tittle” roughly translates as “serif” or the fancy little calligraphic flourishes typical of Tanak manuscripts.)

Religious membership devolves into self-declaration, often of a self-perceived version of the religion one favors. The vast majority of people are born into their religions, an immediate red flag that absolute truth claims will necessarily lead to conflict. And it won’t help to try to devise some Uber-religion that includes all the others, since apart from the occasional Universalist or Bahai, nobody buys that other religions are quite as good (or right) as theirs. Even the task of defining what religion is remains beyond the reach of mere mortals. I find Bronislaw Malinowski’s observation apt, that religion grows “out of the conflict between human plans and realities.” We can imagine a much better world than the one that exists. In some such fantasy worlds, religion itself ceases to exist.

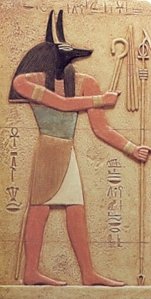

Religion never existed in any pure form. It did not descend from the sky in a unified whole. Instead, religions have been cobbled together by people since the Paleolithic era, and we simply don’t have the time, resources, or influence to go back and start it all over again. Religion may be defined as conflict. Conflict between what is and what ought to be. Conflict between right and wrong. Conflict between us and those who believe differently than we believe. Religion brings, as one founder stated, a sword. Religion gets passed down the generations just as surely as the family jewels and deeds. To ask anyone to relinquish such valued property, even for the sake of world peace, is too much to ask. Even getting people to understand what they claim to believe is too much effort. It is much easier to praise whatever lord and pass the inhumane ammunition.