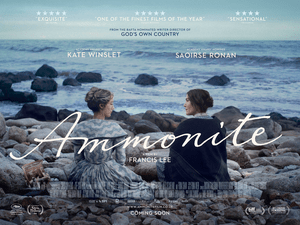

Mary Anning was a real woman. She made valuable contributions to paleontology in the first half of the nineteenth century, although she wasn’t always credited for her work. The movie Ammonite is a fictionalized account of her life at Lyme Regis, where she lived and discovered dinosaur fossils. Being fiction, the movie focuses on how Mary “came out of her shell” by entering into a relationship with Charlotte Murchison (also an historical person, wife of the Scottish geologist Sir Roderick Impey Murchison) who was left in her care when she came down with a fever after trying to recover from melancholy by taking the sea air. Mary had established a life of independence and wasn’t really seeking relationships; her mother still lived with her and, according to the movie, they had a distant but loving regard for each other.

I was anxious to see the film because it is sometimes classified as dark academia. Since I’m trying to sharpen my sense of what that might mean, it’s helpful to watch what others think fits. The academia part here comes from the intellectual pursuits of Anning and the academic nature of museum life (one of her fossils was displayed at the British Museum). Anning, who had no formal academic training, tried to make a living in a “man’s world,” and in real life she did contribute significantly to paleontology. The dark part seems to come in from her exclusion from the scientific community, and perhaps in her love for Charlotte, a forbidden relationship in that benighted time. Of course, this relationship is entirely speculative.

Fictional movies made about factual people make me curious about the lives of those deemed movie-worthy. Ammonite is a gentle movie and one which raises the question of why women were excluded from science for so long. No records exist that address her sexuality—not surprisingly, since she lived during a period when such things weren’t discussed. Indeed, she didn’t receive the acclaim that she might have, had she lived in the period of Jurassic Park. She was noticed by Charles Dickens, who included a piece on her in his magazine All the Year Round, in 1865, several years after her death. These days she is acknowledged and commemorated. This movie is one such commemoration, although much of it likely never happened. As with art house movies such as this, nonfiction isn’t to be assumed. Nevertheless, it might still be dark academia.