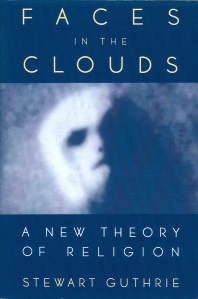

My daughter reminded me that one further aspect that stood out at the Red Mill Museum in Clinton was the persistence of pareidolia. Pareidolia, or matrixing, is the tendency to interpret “random” data as meaningful. More specifically, it is often used to refer to seeing a person (or entity) where it is not. As I wrote in an earlier entry, it has been suggested that pareidolia is the ultimate origin of religion.

For my purposes here, however, I wonder if the sheer amount of false faces we encountered while at the Red Mill might have some connection with the idea that the property is haunted. Somewhat of a skeptic, I am somewhat swayed by ghost accounts since they are so plentiful and since many of those who report them are reputable persons with good observation skills. Ghosts are, however, impossible to separate from some form of religious thought since they are the ultimate examples of the intangible, unmeasurable phenomenon. If there are ghosts in the laboratory, they haven’t been quantified yet.

Old buildings, which abound at sites like the Red Mill, are full of knotholes or other apertures whose original hardware has long since disappeared. Round holes, or spots, as many insects and fish “know” are easily interpreted as eyes. Add a horizontal line beneath your “eyes” and you have a basic face.

Perhaps my favorite example of pareidolia at Red Mill is an old sycamore tree. A large burl on the trunk bears a striking resemblance to a human profile. This is more easily seen in real life where the mind more easily filters out the distracting coloration and focuses on the shape. Since pareidolia is such a fascinating aspect of the human experience of the world, and since it might, conveniently, be tied to religion, this seemed to be as appropriate a venue as any other to share some great examples.